"Our boys Want books”: Camp Libraries during the Great War

When President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany on April 2, 1917, a massive mobilization effort had to get soldiers overseas quickly. Training camps were built throughout the country, and millions of young men traveled far from home for training. Camp life was tedious, and soldiers were often lonely, homesick, and bored. This led some soldiers to pursue “immoral” activities—such as drinking, gambling, and prostitution.

The American Library Association (ALA), the oldest and largest library association in the world, saw this as an opportunity to contribute to the war effort. They felt that soldiers,

“…need diversion and wholesome recreation. They need books to offset tendencies to roam away from camp, to keep doubtful company, to brood and to long for home. The men must be kept in a cheerful, contented frame of mind. Nothing serves better than good books.” (American Library Association, Library War Service. 3)

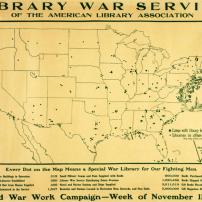

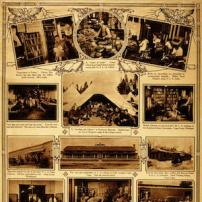

In April of 1917, the ALA established the Committee on Mobilization and War Service Plans. The committee joined six other welfare groups in providing social, health, and entertainment services to camps as part of the Government’s Commission on Training Camp Activities. The ALA also established the Library War Service to provide library services to soldiers and sailors in the United States, France, and other locations. Through grants from the Carnegie Corporation, the Library War Service established thirty-six libraries at bases and training camps.

Grants from the Carnegie Corporation and funding from the Library War Service also enabled the ALA to hire nearly 1,200 library workers. In its inception, women could not become camp librarians, despite the profession being vastly female (women were near 94% of library school graduates from 1888 to 1921). Women were permitted to volunteer and typically worked under untrained male leadership. In July of 1918, seven women protested the sexist guidelines in place at that year’s ALA conference in Saratoga Springs, New York. Soon after, ALA allowed women to hold paid leadership roles in camp libraries.

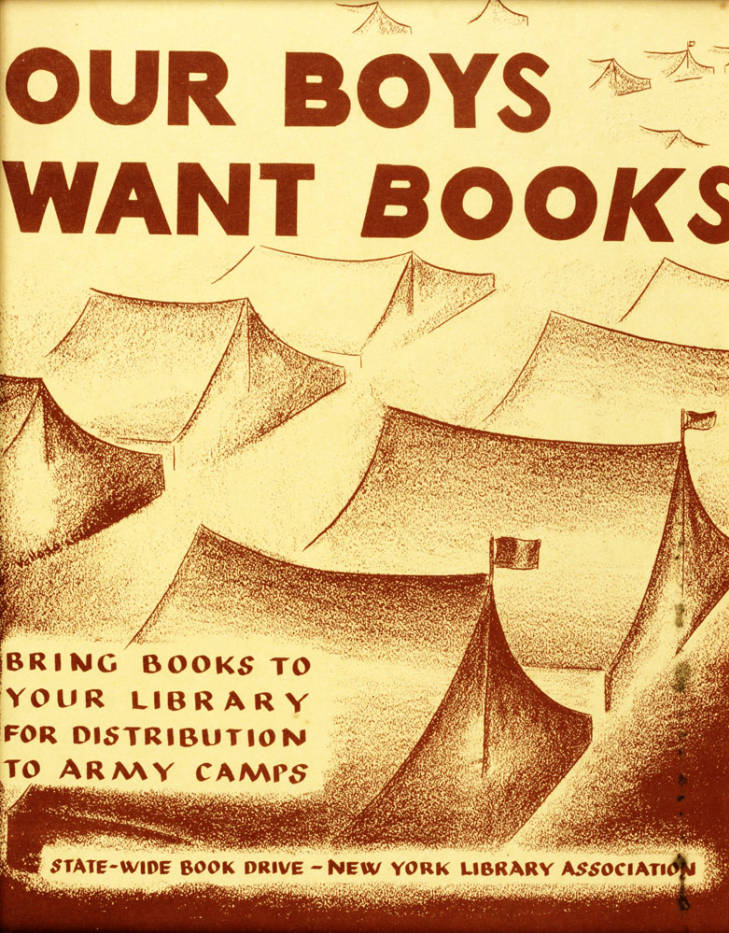

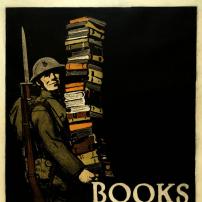

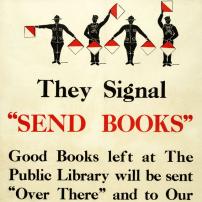

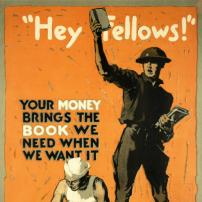

Through the Library War Service, the ALA distributed 10 million books and magazines to soldiers and fundraised $5 million in public donations. Civilians were encouraged to donate reading materials to their local public libraries, and large-scale book drives were held for the Library War Service, however, not just any book or magazine could be donated.

The Library War Service encouraged camp librarians to be selective about the books they kept in their libraries and assured the public:

They believed that reading “good books” could elevate soldier’s moral standards, instill the desire for self-improvement, and promote democracy. They also encouraged specific authors and genres of books to uplift and maintain soldier’s morale.

While soldiers were kept busy during their training with drills and studying, many still found time to visit the camp library during downtime. There were requests for all types of reading materials. Local newspapers were used to ease soldier’s homesickness. Nonfiction books helped soldiers understand the histories of the countries the U.S. was at war with. Technical manuals and textbooks help soldiers boost their knowledge on topics they were learning about at camp.

Libraries were also installed in hospitals to provide books to convalescing soldiers as a diversion from their boredom and pain. Reading materials were even used in hospitals as a form of therapy for “shell shock,” “nervous cases,” and soldiers with newfound disabilities.

Though armistice was declared on November 11, 1918, the Library War Service continued, peaking in April 1919. After the war, professional library departments were established in the U.S. Army, Navy, and Merchant Marines. Other services that the ALA helped establish also continued after the war, like library services in hospitals, which today is under the Veteran’s Administration.