Record date:

Kit Kramer, Department of the Army Special Photographic Office

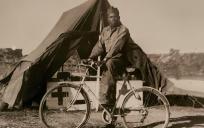

We all come in different shapes, sizes, and builds. At 5’9” and 130 pounds, Kit Kramer was turned away when he requested to join the Military Police, so he applied a skill that he’d been developing since childhood to document the Vietnam War: photography.

Born in Rockford, Illinois, in September 1943, Kramer’s first exposure to photography was when he was handed his great-uncle’s old Kodak camera as a pre-teen. He picked up the hobby and regularly photographed family get-togethers, never thinking it would lead to a military job. Two weeks after graduating high school and uninterested in working in a factory, Kramer was on a train bound for Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri for Army basic training in June 1961. While he had some family who had served, including an uncle in the Korean War and a second cousin in World War II, “It was more something to do,” he says.

During basic training, Kramer was asked to which unit he’d like to be assigned. “For some reason, out of the blue, came ‘’Military Police. Well, he looked at this seventeen year old, 5'9", 130 pound kid, glanced at his paper, says, ‘You don't qualify for that. What else?’” he recalls. Kramer then suggested photography and was sent to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, to study motion picture photography.

Kramer’s first assignment was in early 1962 filming Special Forces’ activity in Laos but was shortly moved to Vietnam, where he filmed US troops training the Montagnards, an oppressed minority in the country’s central highlands. As an eighteen-year-old kid from Northern Illinois, there was a sense of culture shock: “It was like being in National Geographic magazine,” Kramer recalls. He stayed in Vietnam for three months as an assistant cameraman and returned to the States, where he continued to shoot training videos. By chance, though, Kramer was in Panama shooting a jungle warfare training film in October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In December 1965, Kramer was transferred to the Department of the Army Special Photographic Office and was sent to Fort Shafter in Honolulu, Hawaii. He then returned to Vietnam and his assignments varied, but he often covered the 25th Infantry Division in the Củ Chi District. While shooting the division landing along a riverbank, one soldier thought that he spotted a sniper in the trees and called for a rapid deployment strike-- without telling servicemen nearby. The area was targeted by an artillery strike and shrapnel littered the landing zone, hitting Kramer in the back. Fortunately, it wasn’t a major wound, but he did receive a Purple Heart.

While the threat of enemy and friendly fire was always looming, Kramer stayed firm in his commitment to complete his duty. “The way you combat the fear is just by focusing on doing the job, and that's all we did,” he says. “We just did the job. There's always risk. You can walk across the street in Honolulu and get hit by a car, there's always risk. It's just; you focus on doing the work.”

Kramer worked for many years as a photographer with the 221st Signal Corps, with diverse assignments based in Germany and in the US, however his last few years in active and reserve service managing a photo lab did not have the compelling excitement as his previous assignments.

Like his fellow army photographers, Kramer greatly enjoyed the camaraderie and brotherhood that blossomed in DASPO and elsewhere. No matter how long they go without seeing each other, they can pick up right where they left off and have a chat, he says. Kramer also enjoys that DASPO’s work has received recognition and hopes people appreciate the risk war photographers take to complete their duty in every war.

“The tradition goes on and on and on,” Kramer says. “From [Civil War photographer] Mathew Brady and his people all the way down, and they’re all doing good work, and they’re all professionals, and they all just thoroughly love the job.”

Shots of Kramer’s and other DASPO members’ work can be found in “Faces of War: Documenting the Vietnam War from the Front Lines.”

A clip from his interview can also be heard there.