Record date:

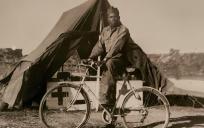

Lieutenant Edward Bales

Oftentimes great danger lurks just under the surface, just out of sight, on knife’s edge teetering with potentiality of tremendous disaster. In Lieutenant Bales' case, this was in a literal sense, as the danger he faced was the very real, predatory threat of Russian sub-marines during his Naval service at the height of the Cold War.

Born in 1939, in the northern Chicago neighborhood of Edgewater, Edward had a happy childhood in a closely knit neighborhood with his parents and two sisters. Since early childhood he had liked to fix with things and enjoyed math and science during primary and secondary education. Partially at the behest of his mother, Bales attended the Illinois Institute of Technology on a Naval scholarship for engineering and participated in summer trips on naval ships and bases as a midshipman, as a part of NROTC. This afforded him a taste of various disciplines in both the US Navy and other branches of the service, but ultimately, he accepted a Naval commission. After graduating and commission as ensign as well as his marriage, he traveled to Glencoe, Georgia for Combat Information Center (CIC) Officer training, where he was educated in navigation, radar technology, tactics, and information processing until 1961, at which point he was assigned to the USS Beale out of Norfolk, with a specialty in electronics. This was at a time of rapidly burgeoning technological advancement, spurred on greatly by the ongoing arms race of the Cold War. At the time submarines were truly coming into their own as a formidable weapon of war, and the US had come ahead with the introduction of the quieter, more efficient nuclear-powered submarine.

Bales served as a part of Task Group Alpha, an anti-submarine squadron, made up of the aircraft carrier USS Randolph and a group of destroyers. These DDE (Destroyer Escort) were equipped with the latest sonar tech, anti-sub torpedoes. He would gain a wealth of experience on submarine technology through exercises the squadron performed between Norfolk and the Caribbean. Bales would be promoted to a lieutenant and CIC officer and duty aboard was typically split between watches as the officer on the deck on the bridge and managing the crew of electronic technicians as the Electronics officer. Constant attention was kept on the sonar systems, as the destroyer escort would keep formation around the USS Randolph.

Bales remembers the amazing sight of watching the planes take off and land on the massive aircraft carrier after a complete patrol. But he would also be witness to a defining point in US and global history on April 17th of 1961, after four months serving on the USS BEALE. His ship and others in the squadron were given orders to reverse course to Cuba, information Bales was privy to at the time as the cryptographic officer. The USS BEALE and the entire task force changed course, only knowing they were to support an invasion of Cuba, later known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, and very little information apart from that. Ed remembers a sister ship, the USS BACHE, and the other ships involved, painted non-existent ship identification numbers to disguise themselves as foreign vessels.

Near Nicaragua, the force then met up with merchant vessels contracted by the CIA to deliver- they only learned later- Cuban rebels- while the military vessels safely escorted them to the coast of Cuba. At one point, Ed was copying air traffic communications between the USS ESSEX and aircraft flying over the beaches, and remembers pilots repeatedly asking permission to engage with Fidel Castro’s forces, ostensibly come to meet this invasion force. It was of course, never given. The counter revolutionaries were no match and the USS Sam Houston, one of the merchant vessels carrying all the invasion supplies, was quickly sunk right in the harbor by Castro’s small air forces. The implanted revolutionaries had no air cover or visibility during the night operation. It would be a foreign policy disaster for the U.S. government and newly elected President Kennedy.

In October 1962, there would come another order for Bales’ ship and others: the USS Coney, the USS Murray, and the USS Randolph, to go south towards Cuba to search for Russian sub-activity as a part of the US Blockade of the area. This came after news of Russian nuclear warheads being brought into Cuba as a response to the United States’ nuclear presence in Turkey. Their sonar eventually pinged against a sub, and its identity was confirmed by an intercepted Russian radio communication from the vessel. The ships in Bales’ squadron pinwheeled around the location, preventing the Russian sub from surfacing. This submarine, like many of the USSR’s at this time, was diesel electric, and had to resurface to recharge its batteries.

Bales and even the U.S. government would only find out much later what dire circumstances could have resulted from this interaction, as the torpedoes the sub had equipped were nuclear tipped. Initially, the vessel had been ready to fire them, but for whatever reason, the Vice Admiral Arkiphov (Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov/Василий Александрович Архипов (1926 – 1998) was a Soviet Navy officer credited with preventing a Soviet nuclear strike during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Such an attack likely would have caused a major global thermonuclear response), having had lost contact with Moscow, chose, thankfully, not to authorize their use. A few days later USSR Premier Nikita Khrushchev and President Kennedy would come to an agreement that would remove the nuclear warheads stationed in Cuba, while the U.S. would ostensibly remove their own from the Turkish border. This information has only been made public in recent years. Bales would leave active duty at rank of a commissioned Lieutenant for service in the reserves in 1963, after these eventful years at sea.

He and his wife Barbara would move back to Chicago, where Ed began working for the Motorola Corporation for the next forty-seven years. In this time, they would raise four children. Today, Ed still actively keeps up with events in the US Navy and recognizes how pivotal a part it played in the major conflicts of the Cold War, although much of that only became truly apparent years after. Though the Bay of Pigs had been a public relations disaster, he believes that the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis had been dealt with an appropriate amount of forcefulness and resourcefulness by President Kennedy, that prevented further Russian agitation. He feels that those who serve in the US military understand public duty and service in a way that greatly puts major global and domestic events into perspective.