Record date:

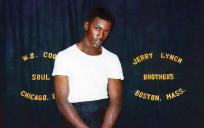

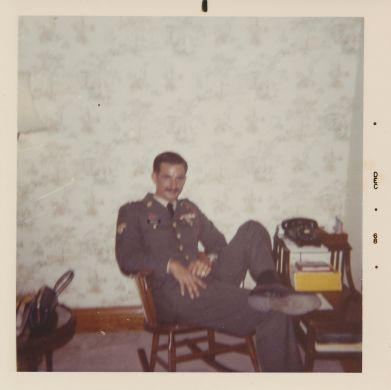

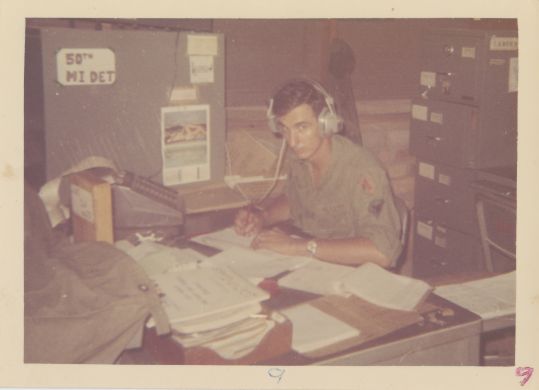

Captain Neal Morgan, 1st Infantry Division

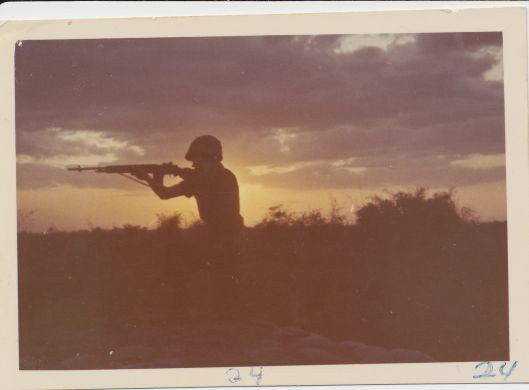

From playing baseball in the local park to dodging bullets zipping past one’s head in the jungle, each and every Vietnam serviceman experienced a reversal of life as he had known it. In spite of the desire to fulfill their duty, many Vietnam veterans, such as Neal Morgan who has seen the horrific consequences of war, conclude that it should only be used only, as a last resort.

Morgan grew up in Oak Park, Illinois, a western Chicago suburb. He is the oldest of four children with two brothers and one sister and recalls his upbringing fondly with schools and parks within walking distance of his house. Morgan’s mother stayed at home to raise the kids while his father worked as a foreman at Dean Foods, which called for late nights, leaving little family time. But Morgan calls his father a “great provider,” which created a “very pleasant lifestyle” for his family. His father also served in the Army during World War II but never went overseas because of hearing problems.

Morgan was drafted into the Army in April 1967 but had two previous deferments after receiving draft notices. Unknown to Morgan at the time, his mother called anyone who would pick up the phone and pleaded to prevent her son from going to Vietnam because the body counts were rising and, “she was absolutely terrified of the whole situation,” he says.

Morgan was sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky, for basic training and excelled in his placement testing. After heavy resistance, he was persuaded to join Officer Candidate School [OCS], which extended his service for two years, and went to advanced individual training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. But Morgan was unhappy with the unequal treatment of the men. “I just didn’t understand the mindset,” he recalls. “It wasn’t logical to me.” So he resigned from OCS.

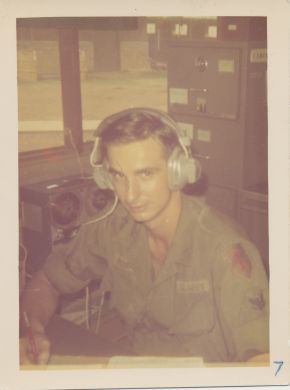

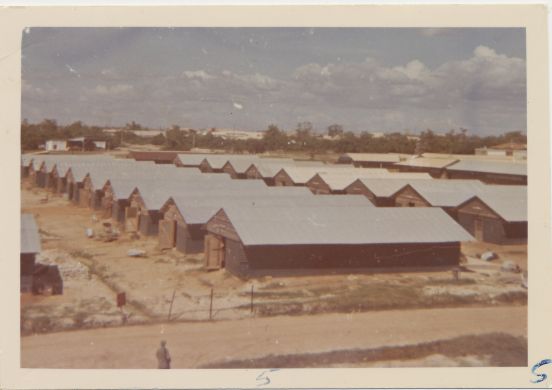

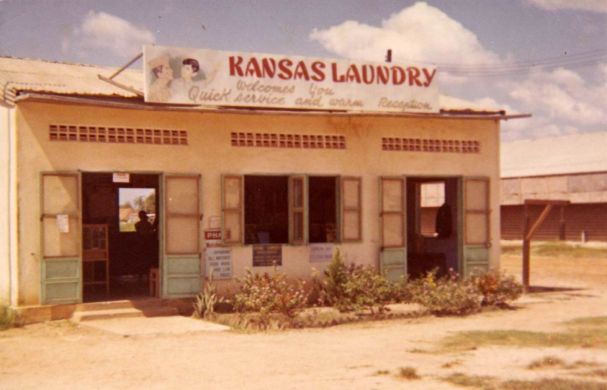

After training, Morgan was sent to Vietnam and was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division, where he worked at its headquarters as a finance clerk, but the administrative role didn’t mean that he did not see combat. For example, while walking to the Post Exchange one day, he heard a bullet zip past his head, but he was shocked so that he didn’t realize what was happening until, “I saw a bullet plow into the dust in the pathway in front of me and thought, ‘It’s time to hug the ground,’” he laughs. Another incident was when Morgan and his squad came under fire while on a perimeter sweep. He found cover behind a fallen tree and the sergeant shouted, “Don’t fire! We’re in a no fire zone! I said, ‘Tell them that,’” he laughs. But Morgan disregarded the sergeant’s orders and fired two rounds from an M79 grenade launcher. He didn’t receive any punishment for his actions, instead, he received the Bronze Star. The unexpected Tet Offensive did not ignore his base camp Dĩ An, either.

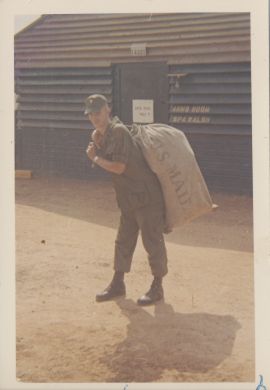

As a finance clerk, Morgan handled payroll and also processed troops both coming and leaving Vietnam and delivered letters from home to soldiers. One letter he delivered, though, was a Dear John letter. Frantic by the news, the man went back to his bunk, and started shooting the roof. They surrounded the building and asked that he come out, but he threatened to shoot anyone who came in. “He was just distraught,” Morgan says. “He was totally gone.” A sniper was brought in, and he shot the distraught soldier in the shoulder; however, it also hit his rifle and a shrapnel plunged into his neck, killing him quickly.

When Morgan returned home, he found work in sales, got married, and had a daughter. Unfortunately, the marriage didn’t last, but Morgan remarried, has a step-daughter, and he and his second wife celebrated their thirty-eighth anniversary in September 2018.

Morgan feels he matured greatly while in the Army and time in Vietnam but firmly believes war is an absolute last resort. In fact, this was the main impetus for him writing his memoir, Shot at & Missed: Vietnam October 1967 to November 1968. There has been and will always be conflict, he says, but in war, there’s no resolution and nations should always seek a more peaceful route.

Since the interview, Neal Morgan has, unfortunately, been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, one of diseases that the VA has recognized as a result of Agent Orange exposure during the Vietnam War. He is currently in remission. Morgan invites those interested to check his website Shot At & Missed for additional information.