Record date:

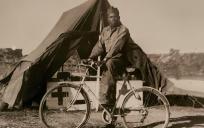

Carl C. Hansen, SGT

Every summer growing up, Carl Hansen and his family would pile into a car for a two-week vacation. The six of them would drive from Montana to Nebraska, to Canada or to California -- to name a few destinations. The trips, which involved visiting relatives or supporting Hansen’s father’s military career, cemented in Carl a love for travel that would help support his future career in photography. Hansen served in the Department of the Army Special Photographic Office (DASPO) from 1967 to 1970, and eventually became the Director of Photography for the Smithsonian. Hansen’s photographic work speaks for itself and is a testament to the talent and skill of the men that served with DASPO Pacific during the Vietnam War.

Hansen was born in Sidney, a small town of less than 3,000 people on the Eastern edge of Montana, near North Dakota. Growing up in town rather than on a farm, the self-described ‘city-kid’ played football, went hunting, and held several jobs, including being part of the first survey crew for the state of Montana, working on numerous farms, and a position as a hotel desk clerk. Hansen’s mother was a nurse in the maternity ward of a local hospital. His father had served in the military as part of the Rainbow Division in the Philippines during World War II, translating this experience into a postwar career as the chief of police of Sidney, Montana, and then as a lieutenant colonel in the Montana National Guard.

After graduating from high school in 1966, Hansen enlisted in the US Army in the hopes of receiving the best education his limited finances would allow. He wanted to pursue a career in architecture, but the Army did not offer any schools in that discipline. Hansen instead chose to pursue photography, something he was somewhat familiar with, as he had occasionally fooled around with his parents’ cameras.

Hansen trained at Fort Lewis, Washington, and then cinematography training at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey. His time spent there was studio oriented and focused on basic instruction in storytelling and aesthetics, though it also gave him a good foundation in the mechanics of photography. This training served Hansen well over the years. His ability to tell a story with pictures enabled him to more effectively capture the emotional impact of a given moment. In November of 1967, Hansen shipped out to Fort Shafter in Hawaii. Although at first a little overwhelmed, Hansen quickly settled in comfortably with his fellow members of DASPO, holding himself to a high standard of performance. During the two years that he was with DASPO, Hansen served five tours. His first, third, and fifth were to Vietnam, his second was to Thailand, and his fourth was to Korea. On his first tour to Vietnam he was cross trained as a still photographer and went on missions as needed either as cinematographer or still photographer. Hansen believes his position as a member of DASPO put him in a unique, flexible position that allowed for a broader understanding of the war effort. Having the freedom to travel across the country helped him capture the nuances of combat and life on the front, though looking through a lens was a vastly different world from looking through the sight of a gun. The time Hansen spent wandering around different regions of Vietnam and his extensive contact with the local population enhanced his understanding of the war.

Some of Hansen’s notable work includes images of the Tet Offensive, pictures of President Nixon’s first visit to the combat zone, and the arrival of the first National Guard Unit in Vietnam. He also shot several documentaries, including one on an experiment devised to study the effects of modified jungle boots on the prevalence of jungle rot, as well as another on the US Army mortuary in Saigon.

After he returned to the United States, Hansen attended the University of Montana, planning to transfer to the University of Missouri to finish his degree. Before he transferred, he received a job offer from NBC. He worked at NBC for three years, but his frustration with the transition to digital equipment led to his departure and a subsequent career in newspaper photojournalism. Another tipping point for Hansen came from a black-tie social event he was required to photograph year after year in the oppressive summer heat of Naples, Florida. Fed up with the newspaper business, Hansen applied for and received a temporary position with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Center in Panama, which then transitioned into a full-time, permanent position. He remained in Panama for seven years, photographing research expeditions in the jungle and underwater, and witnessing the US invasion and removal of Noriega in December of 1989. In 1992, Hansen transferred to Washington, D.C. and made Chief of photography of the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History. Then in 2002 he was promoted to Director of Smithsonian Photographic Services. Though he missed being behind a camera, he continued to thrive in this position until his retirement in 2008.

Hansen wants to remind people of the dedicated research that goes on in the Smithsonian -- it’s more than just a museum -- and of the efforts of the DASPO photographers. For him, DASPO was not just about documenting the reality of combat but capturing the experiences of the people involved.

Glimpses of his work, including his iconic shot of a landing of a Huey helicopter amid purple in the smoke can be seen in the web exhibition, Capturing the Faces of War.