Record date:

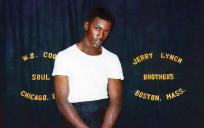

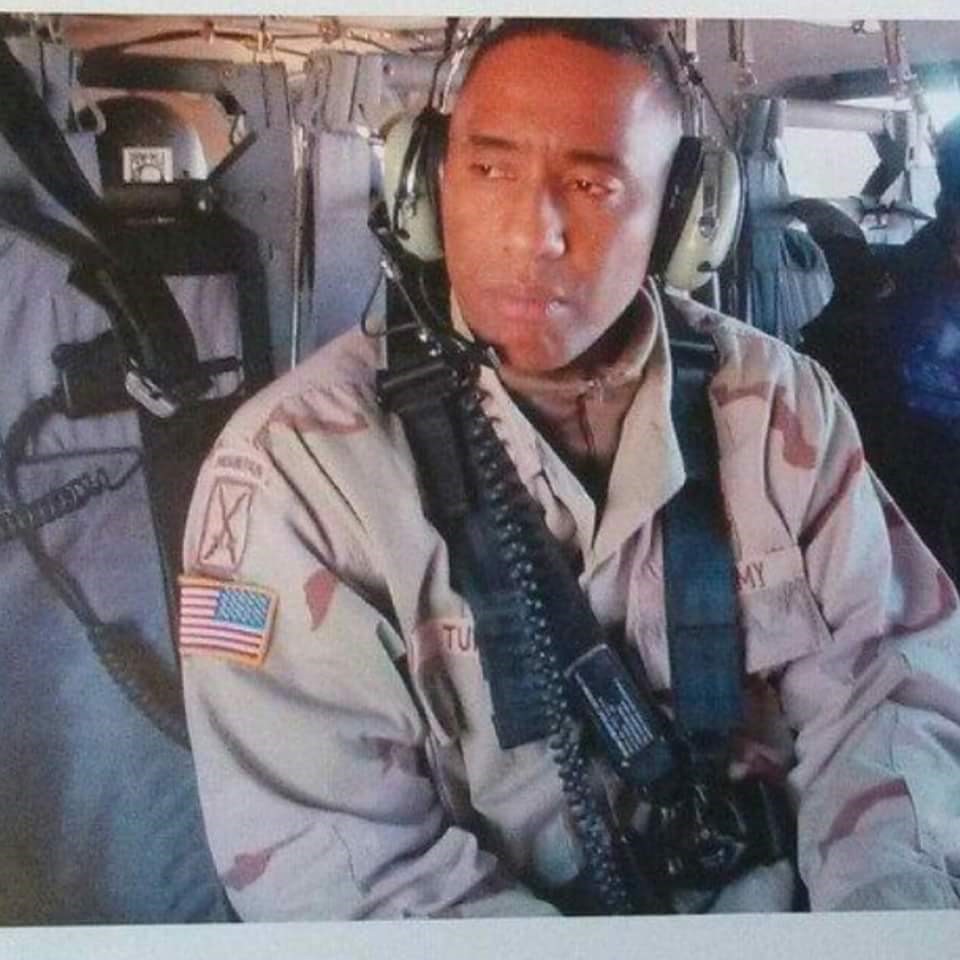

Hughes Turner, Colonel

In this five-part oral history, Colonel Turner shares his storied career and his reflections.

Part 1

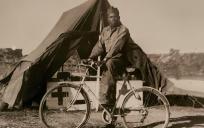

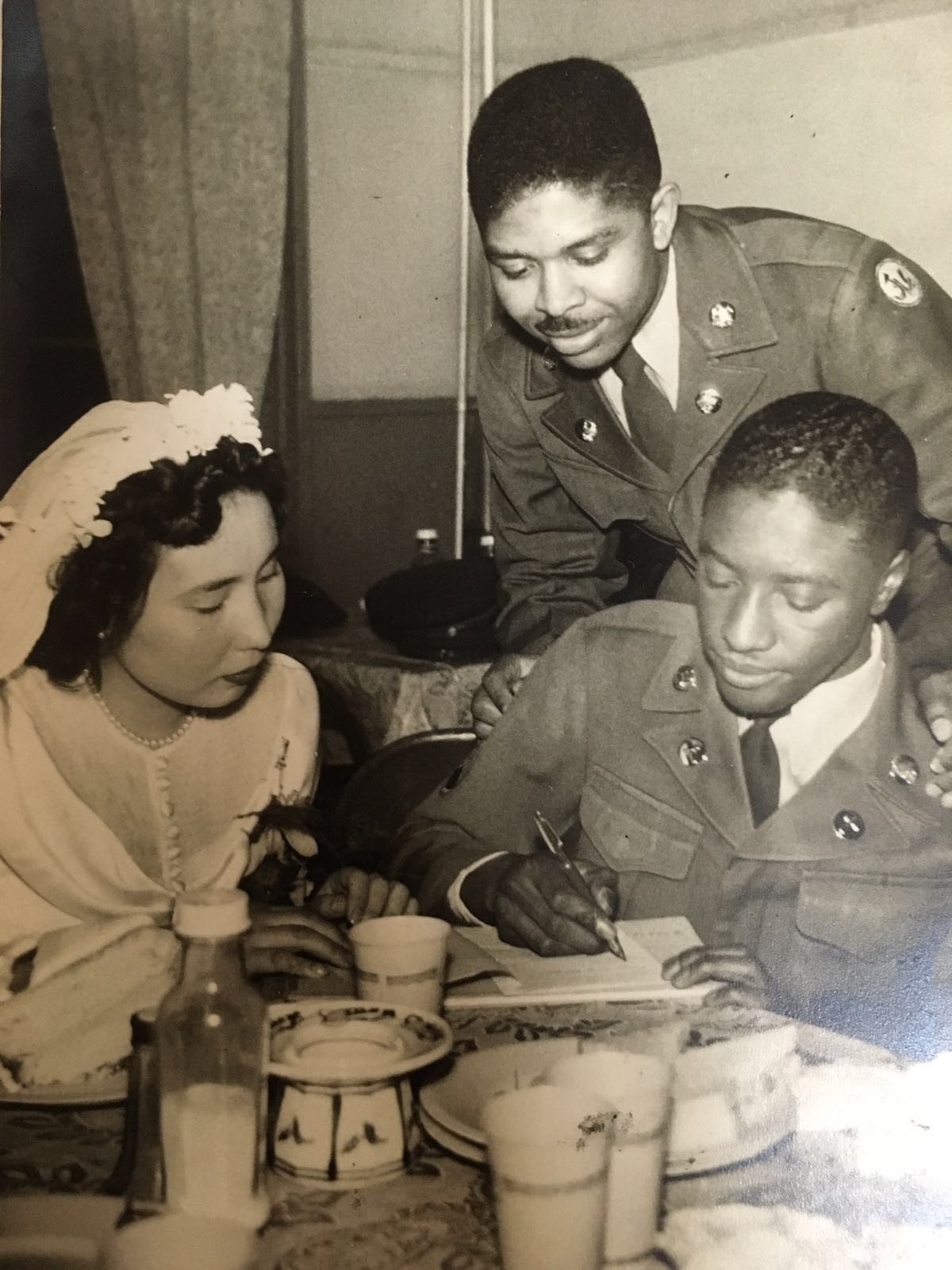

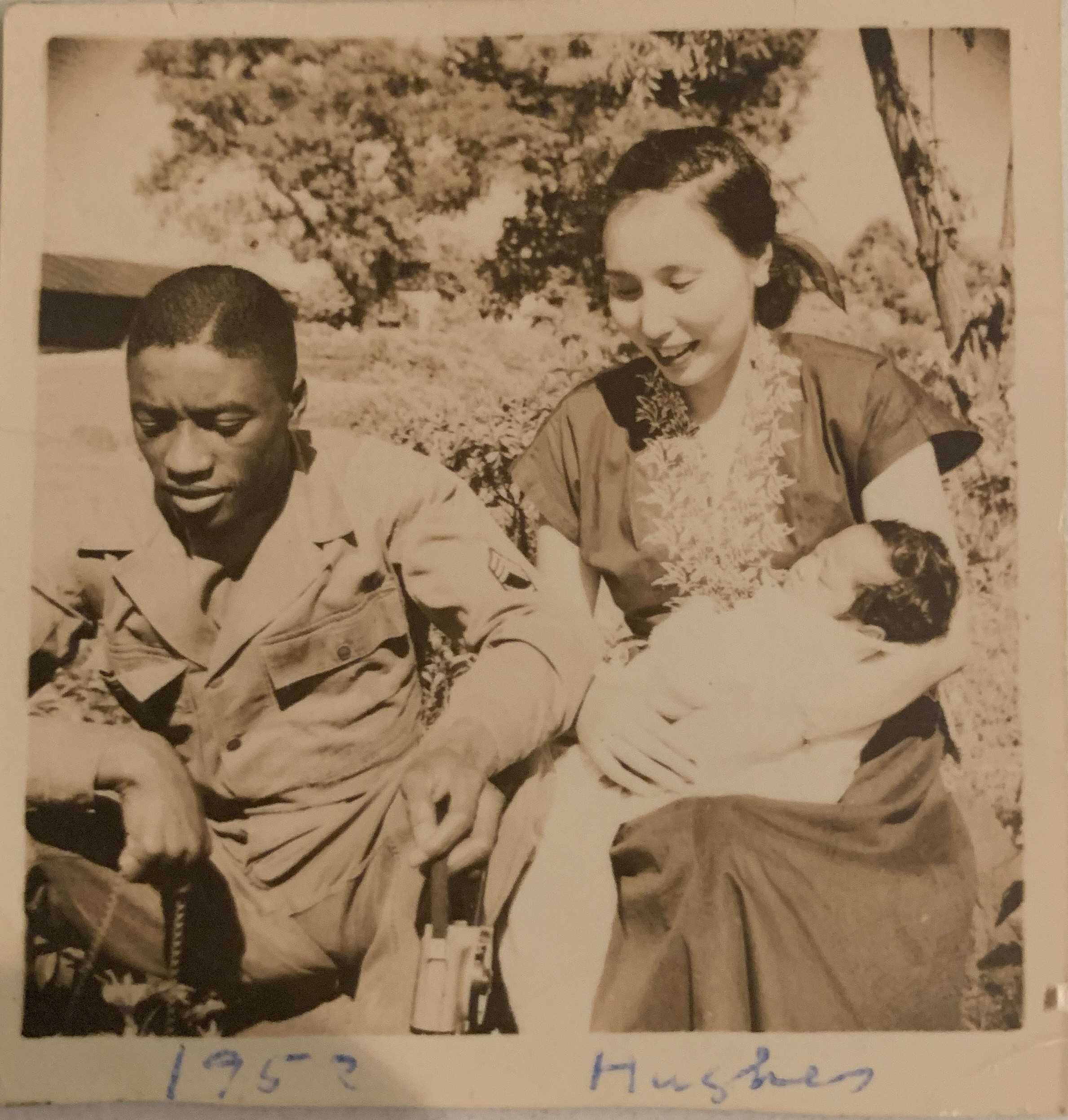

As a son of an African-American active-duty Army father and a well-educated Japanese mother who met in Occupied Japan after World War II, Hughes’ youth offered exposure to a multiplicity of cultures and viewpoints. Additionally, when living in Germany during the Cold War, the Turners would travel with their sons to places of significance such as the Berlin Wall. During his high school years, Hughes’ father accepted a post in Okinawa, relatively close to his wife’s family on the mainland, ensuring that the children would not move during their high school years. Okinawa was a major staging area for Vietnam. Dissent about the war and civil rights was felt keenly there and did not escape Hughes and his father. Hughes was pleased that he was awarded a four-year Army ROTC [AROTC] scholarship to a civilian institution of his choice and could forge his own path.

Part 2

Hughes began studies at Texas Christian University but found the ambiance there too conservative and transferred to the University of Washington, Seattle. Between his junior and senior years in AROTC, Hughes participated in the Army advanced summer camp (basic training equivalent) at Fort Lewis, Washington. His excellence at military craft and insights gleaned from a Black combat infantry officer mentor there were pivotal.

After graduation, in January 1975 Turner attended the Armor Officer Basic Course at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Turner’s first assignment was with the 1st Infantry Division, 1st Battalion, 63rd Armored Regiment, at Fort Riley, Kansas. Additionally, Turner became both Airborne and Ranger-qualified, at Fort Benning, Georgia. It was there that he witnessed the distress of South Asian soldiers whose families were stranded in Vietnam after the US withdrawal in April 1975.

As the only Black armor platoon leader in a division of twenty thousand troops, Turner’s next staff assignment as EEO [Equal Opportunity Employment] Officer at the Division Support Command, at Fort Riley was sorely needed. One highlight was forging an acquaintance with Alex Haley, author of the seminal work Roots, whose permission, he sought for the use of video recordings in the 1st Division’s EEO studies program.

He was then assigned as the executive officer for the headquarters company, the 4th Battalion of the 63rd Armored Regiment. His next role as battalion adjutant (for the 4th) involved duties of personnel and human resources support for the battalion. Turner was discharged in 1978.

Next, he studied law at Berkeley University and also served in the Army Reserves, 91st Training Division. Although law school was intense, he participated in the Black Student Law Student Association as its president, volunteered for the Steet Law Program, and made a point of going on outings with his wife. After graduation, Turner accepted a position at the law firm of Kilpatrick and Cody in Atlanta, Georgia, as an intellectual property attorney. He also joined the Army Reserves at Fort McPherson, assigned to the 3rd Army headquarters which later became the land component of the U.S. Central Command.

Turner was selected for active duty through the Active Guard/Reserve [AGR] program. Now, Major Turner was assigned to the Army ROTC department at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He feels gratified that many of the ‘kids’, now colonels and generals have reconnected with him in recent years.

He was scheduled to deploy to Saudi Arabia for Operation Desert Storm after his AROTC assignment but at the last minute, received orders to report to the Office of the Chief, Army Reserve in the Pentagon.

Part 3

Colonel Turner now operated at the national level. For example, he was responsible for the board-level selection of officers throughout the country, to attend military higher education schools/courses which included securing seats for officers to study at prestigious civilian universities. Turner expresses gratitude to formal and informal mentors, including those who saw potential in him. There were others like Colin Powell, then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs whose charisma, modesty, and humor he greatly admired.

Turner agreed with cycling up of field officers to the Pentagon and then returning them to the field to keep the defense thinking fresh. He returned to the “Pentagon of the South” Fort McPherson, this time to the DCSOPS [Deputy Chief of Staff Operations] at the U.S. Army Reserve Command [USARC].. His wife found a job as a university professor in nearby Atlanta and his children were in middle school.

An enriching year followed when he was selected for a one-year National Security Fellowship at the Kennedy School at Harvard University. After that, he led the Training Division at the USARC.

Part 4

In 1998, Turner was chosen to command an Army Reserve brigade as part of a new program that allowed active-duty officers to command National Guard and Reserve units. He saw first-hand the effect of mobilization on the civilian workforce. For example, many of his military police units drew from the civilian police force of a particular city thus leaving the local police short-staffed.

Because several of his military police units were mobilized to Bosnia-Herzegovina’s, “Support and Stability” Operations, Turner did site visits there. Flying into war-torn Sarajevo, with mountains surrounding the city, not to mention atrocities on display at the Olympic ski jump site, was not for the faint of heart. Turner also met General Eric Shinseki [a future Army Chief of Staff] there who was a prolific reader/learner, whose knowledge reinforced Turner’s view that “When you’re at war, you go to war. When you’re at peace, you go to school.”

Turner was then asked to head the Retention Division within the U.S. Army Reserve Command at Fort McPherson. He then rose to the position of Senior Army Reserve Advisor liaison to the Commanding General of the 3rd Army under Lieutenant General PT Mikolashek in the summer of 2001. Things started out routinely, preparing for Bright Star, the bi-annual training exercise with the Egyptian military, and participating in staff briefings in the Middle East. Although OPLAN 1003 focused on contingency war plans in Iraq and Iran 3rd Army and CENTCOM had already established a forward presence in Kuwait and Qatar respectively, Afghanistan was seen as a “footnote”.

The 9/11 strikes, and in hindsight, the 9/9 assassination of Afghani leader, Ahmad Shah Massoud, made it apparent that the perpetrators were tied to the Taliban and al-Queda. Thus 3rd Army commanders were ordered to deploy combat troops to link up with CIA elements and begin combat operations in Afghanistan.

Turner was responsible for identifying the Army Reserve forces necessary for the war such as the 335th Signal Command and 3rd MEDCOM. As he previously noted, there was a transition from considering Reserves and Guard as “weekend warriors” to full-time deployable forces. He describes the scramble as a “come as you are war.”

In December 2001/January 2002, Turner was sent to Karshi-Khanabad [“K2”], Uzbekistan, a major staging base for Operation Enduring Freedom [OEF], the war in Afghanistan. The logistics were complex, be it negotiating basing rights, obtaining rail permission to move supplies through multiple countries, or resolving discrepancies between different pay systems [active vs. Reserve/Guard] so that troops could get paid. K2 was also on the site of a former chemical dump where Turner probably developed his “Afghanistan cough.” Flying on a C-130 at night to Kandahar where the crew dropped everyone off while the engines were still running due to hostilities was also part of a “day’s work”. Sadly, the gunfire that he heard when disembarking resulted in the death of soldiers from Canada’s Princess Patricia Battalion due to friendly fire. He was impressed how after the memorial services, the battalion immediately pressed on with their combat mission.

At Bagram Air Base, Turner witnessed the agonizing decision made by General ‘Buster’ Hagenbeck not to send any rescue aircraft at night to a group of pinned-down Rangers in order to prevent further loss of life at ‘Roberts’ Ridge.’ This was part of Operation Anaconda, the first ground mission of conventional forces [vs. special forces] to strike against the Taliban and al Qaeda in the Shah-i-Kot Valley, to block the enemy’s escape to Pakistan. Watching the events from then cutting-edge drone video streaming was equally painful since unlike today there was no way of remotely striking back.

As time passed, he noticed that OPLAN 1003V was becoming more oriented to Iraq. For example, troop levels were capped at 8,000 for Afghanistan, and requests to mobilize specific units for the Afghanistan operation were denied.

Turner was reassigned as the executive officer and deputy chief of staff for the Deputy Commanding General of CFLCC [Coalition Forces Land Component Command], which resulted in his more intense involvement with US basing rights in preparing for Operation Iraqi Freedom [OIF].

Part 5

Because Part 5 took place in August 2021, during the final phase of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, Turner shared his reactions. He was disturbed that the evacuation was handled in a chaotic fashion, abandoning people who could have been rescued. It should have been a classic NEO [non-combatant evacuation operation]. In his opinion, more sizable troops elements should have been deployed earlier in order to secure the withdrawal. He draws many parallels to Vietnam, but at least now, the American public was able to separate the “warrior from the war.”

Turner also reflects on the war in Iraq, noting that the readiness of troop units never reached the “green” rating indicating that they were completely “good to go.” He also emphasizes the variegated support of the Reserves to this war: engineering units, South Carolina National Guard crews flying the A-10 Warthog, bombing aircraft, and US Department of Agriculture personnel ensuring that equipment was cleaned properly before being returned to the States.

Turner was in Iraq during the first few weeks of Phase 1 combat operations. He traveled in a Humvee, evaluating the main supply route along Highway 80 from Camp Navistar toward Baghdad. At that stage, he and other commanders were concerned with troop complacency, because of periods of relative calm during combat operations.

Unfortunately, IEDs [improvised explosive devices] started to manifest themselves a few months later, becoming more lethal as time progressed. Turner noticed that the resurgence in the fall of 2003 was unexpected by the US Army as there had been discussions about the re-deployment of the 3rd Infantry Division to the US in the Fall of 2003.

Always attune to history, Turner found his visit to the Ziggurat at Ur, the root of the three Abrahamic faiths [Judaism, Islam, Christianity] going back thousands of years, very moving whose tangibility reminded him of picking up a piece of cinder block from the Berlin Wall as a child.

He shares his reflections on civilian Iraqis, and British troops and underscores the complexity of urban warfare in a city like Baghdad which was operationally divided into fifty-six districts during its takedown. He also covers the conference he attended at his alma mater at Berkeley Law School, on “enhanced interrogation.” Turner points out that commanders are concerned with Force Protection, which includes PTSD. He too finds his monthly talks with his mental health counselor helpful and takes solace in art. Reproductions of two works by Japanese 18th-century artist Hokusai that he commissioned a respected Japanese artist to do, hang on his walls.

Turner’s return to civilian life was dramatic. His phone job interview for an SES position [Senior Executive Services] at the US Office of Personnel Management was interrupted by a mortar attack. After two years at OPM, he helped stand up the Office of Director of National Intelligence [ODNI], and then at the National Counterterrorism Center [NCTC] in D.C. In 2011, then Secretary of the VA Eric Shinseki invited Turner to join the organization as his deputy chief of staff where he was assigned for several years.

Turner has a son and a daughter. Like his father, he made sure that his children did not move around during their high school years though he was compelled to be apart. Turner made sure to write a death letter to the family and add a dog tag to his boot in the case of the worst scenario.

Turner’s understanding of a Citizen Soldier is one who commits his time to the greater good. Even in his retirement, he lives this out by serving on several nonprofit boards of directors including the National Veterans Art Museum [NVAM], the Veteran Breakfast Club (VBC), and Kids Rank.