Record date:

Gerald Goodman, Captain

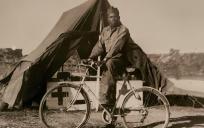

At a mere seventeen years of age, Gerald Goodman started his military career in 1938 as part of the 110th Engineers 35th Division of the National Guard. He continued in his US Army service from December 1940 until January 1946 as a member of the 20th Combat Engineer Regiment 2nd Battalion and finally of the 20th Engineer Battalion. He participated in campaigns in Africa, Sicily, and Europe, including D-day.

Born to a tailor and housewife, Goodman grew up speaking Yiddish and his family was very active in the Kansas City Jewish Community. As a child, Goodman was interested in math and sciences, choosing to study engineering at a junior college in Kansas City. Goodman, who was part of the ROTC in high school, joined the 110th Engineers 35th Division of the National Guard in 1938, in part, to pay for junior college tuition. The 35th Division was called into federal service on December 23, 1940.

Goodman was transported by train to Camp Robinson in Arkansas, where he and the 110th Engineers Regiment built on their engineering training and simulated large scale-military maneuvers in October 1941. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Sergeant Goodman applied for Officer Training School and was accepted. Following his graduation at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. Goodman was assigned to an engineer depot company where he remained for several months before he was selected to go the 20th Engineer Regiment at Camp Blanding, Florida in summer 1942. Following that, Goodman and the 20th were ordered to Fort Dix in New Jersey in Fall 1942, where they would likely go to Europe. Instead, they would be part of the Allied invasion of Morocco, then controlled by Vichy France.

The amphibious invasion at Fedala, near Casablanca, met with hardly any casualties. Once in Casablanca, the 20th were bivouacked in what was once a hippodrome. They provided labor to unload ships in the port of Casablanca for several months. In March 1943, Goodman was part of the motor march over the Atlas Mountains toward the Mediterranean. It was necessary to remove the mines in along the roads and road shoulders. This was treacherous work. On one such occasion, several of Goodman’s platoon suffered mortal casualties and injuries when an S-Mine (aka a “Bouncing Betty”) exploded out of the ground and detonated scattering shrapnel in a 25-foot radius.

Following the German surrender in July 1943 in North Africa, Goodman and the 20th got word that there were designated to take part in the invasion of Sicily, travelling on a LCI [Landing Craft Infantry] without encountering artillery. There, Goodman was temporarily assigned to regimental headquarters. He was made detachment commander at the regiment’s forward command post where he led a small group for several weeks, whose mission was to open the lines of communications near the points of action.

In November 1943, Goodman learned that he would go to England and get ready to invade France. As he journeyed there, Goodman contracted hepatitis, and remained in ship sick bay during the journey, and was hospitalized once they landed. He received excellent care during his month-long recovery and rejoined his unit in January 1944.

The regiment was reorganized, and Goodman was assigned to the 20th Engineer Battalion. The battalion received orders that they would participate in the invasion of France. This would be their third amphibious invasion, and they were selected due to their experience. Goodman crossed the English Channel during the wee hours of June the 6th., landing a few hours after H-Hour, “We got onto the beach and there were some high ridges that we hid behind, so that we weren't in direct view of the enemy… we were subject to mortar fire and artillery fire”. Goodman, as supply officer, stayed at the battalion headquarter and was in charge of the supplies requisition and fulfilment operation.

As Goodman and the 20th made the way across France, they arrived in Paris just after its liberation on August 26, 1944. Of that experience, Goodman says, “I remember riding in a Jeep and women holding up their babies for us to kiss, so that they could say that a liberator kissed their baby.”

Goodman participated in the Battle of the Bulge, and later crossed into Germany Germany at the Remagen Bridge. He and the 20th later moved east through Czechoslovakia, where he encountered Russian soldiers, socially, in Prague. Throughout the advance, Goodman recalls that while he did not encounter any concentration camps himself, he and his unit, knew about the camps both from news reporting, and they experienced the horror of the camps when they moved through unmistakable strong odors of burnt human hair

Goodman was a faithful correspondent to his family; he and his father wrote letters to each other dedicatedly, and this correspondence has been saved by the family. Goodman also reveals how, as a lieutenant, he, like all officers, were censors of the enlisted men’s mail.

On their advance across Europe, Goodman and the 20th would occasionally encounter a German supply depot, where they collected war-time souvenirs. Goodman took an SS dagger, and a crate of Czechoslovakian crystal stemware emblazoned with swastikas. He had a plan for these goblets from the SS officer’s commissary. They would be re-purposed as the traditional glasses to be broken at Jewish wedding ceremonies of his future family. This is a tradition that the family has cherished.

As a Jewish participant, Goodman reflected on his fellow servicemen’s attitudes and how the US Army went to great lengths to allow Jewish GIs to observe Jewish holidays, such as organizing prayer services. The Army also gave every Jewish soldier a box of matzah, as well as wine to share during Passover.

Following VE Day, Goodman had enough points to return to the States rather than fight in Japan. Following his return and several months of earned leave, Goodman was discharged from the service in January 1946. It took Goodman some time to reacclimate to civilian life, and he enrolled in the University of Illinois in early in 1946 to study engineering, using the GI bill. Goodman did not attend his graduation ceremony in 1947—instead he was readying to be married. Goodman began to work as an engineer and the couple had four children, present at this interview.

Of his time in the service, Goodman reflected that the best survival technique was to keep one’s perspective and, “maintain the proper attitude no matter what you have to endure.” Hearing the Star-Spangled Banner at military assemblies always got to Goodman, it was a reminder that, “what you were doing was worthwhile and what you were preserving was worth preserving.”