Record date:

Peter “Rupy” Ruplenas, Sergeant

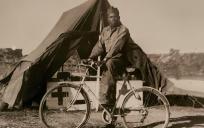

Through three consecutive conflicts (World War II, Korea, and Vietnam), Peter “Rupy” Ruplenas took photographs for the U.S. military so that intelligence would understand what was going on—first as a part of the Signal Corps and then later as a member of DASPO (Department of Army Photographic Office).

Peter Ruplenas was given a task in the military that many men in a combat situation would have scoffed at: instead of being given just a weapon, he was handed a camera and told he was going to be a photographer for the military. Born in South Boston on October 5th, 1918, and originally joining the Army Air Corps months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred, Mr. Ruplenas went to basic training and was at first given the clerical job of a “general flunky,” as he recalled it, before being sent to a two-week Photography School at Davis-Monthan Army Air Field in Arizona. Afterwards, he was shipped off to England, serving as a combat photographer with the 486th (Heavy) Bomb Squadron. In his oral history, Mr. Ruplenas discusses learning how to time the movements of the Squadron so that he was either taking photographs of the bombs falling towards their intended target or taking photographs of how successful the bombs had been in hitting the target. These images would be sent off to “Intelligence” and would be the basis for future training and other missions. Mr. Ruplenas was actually on one of these bombing raids over Normandy during the D-Day invasion. In total, he went on six of these bombing raids—risking his life to take photographs in order to advance the war effort—before going back to Boston after WWII.

While most would consider that the end of any obligation for service, Mr. Ruplenas actually reenlisted once the U.S. entered the Korean War. While the conditions in Korea were almost unimaginable—Mr. Ruplenas, for instance discusses the drastic shifts in weather and how he suffered from frostbite—according to his interview, the photographers were at least well supplied with film even when other supplies were lacking. Mr. Ruplenas went through a lot in Korea: he describes being blown up into the air because of a tank being destroyed 50 feet in front of him and how he lost his hearing from the concussion of the loud shelling all around him. In Korea, Mr. Ruplenas was often put into precarious situations (mostly of his own choosing); he was attached, for example, to the 7th Infantry Division and went with an anti-guerrilla team known as the Rice Raiders behind enemy lines, documenting as the Raiders destroyed weapon caches.

After Korea, Mr. Ruplenas reenlisted once again as the Vietnam War broke out. Still, throughout his oral history interview, Mr. Ruplenas wanted to make it clear that he didn’t think of himself as a hero—simply someone that was giving heroes coverage that would be used by Military intelligence to help in the fight. In Vietnam, Mr. Ruplenas became a part of DASPO—the Department of Army Special Photographic Office—an Army unit that was made up solely of photographers and filmmakers doing the kinds of work that Mr. Ruplenas had now been doing for three consecutive conflicts. In subsequent oral history interviews conducted with members of DASPO, all were quick to acknowledge the huge role Mr. Ruplenas played in helping train others and about the level of his talent: his photographs were routinely rated the highest, a subject of “envy” among the other photographers engaged in friendly competition.

In addition to his combat photography, Mr. Ruplenas was also involved in documenting procedures at the White Sands Missile Range before his retirement in 1970. He also spends time in his oral history interview discussing what it was like to photograph some of the biggest celebrities of his day: Frank Sinatra, Johnny Cash, and Robert Mitchum to name but just a few. In his retirement he spent his time with his son and other family, traveling to attend Veteran functions all over the country, and putting together three books of his photography.

Peter “Rupy” Ruplenas passed away April 16, 2016. He left behind many family, friends, and colleagues, as well as an important body of photographic work that depicts everything from important details about military life to the horrors associated with war. We thank him for his service and the impact he had on our understanding of the military.