Record date:

Chuck Meyers, First Lieutenant, Military Intelligence

From entering the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps to foreseeing the Tet Offensive to teaching history in middle and high school, Chuck Meyers’ life has been filled with a multitude of exciting and tormenting experiences.

Born in Chicago in 1944, Meyers’ father served in the Illinois National Guard during World War II. His father was immensely patriotic, but could not be drafted because he wore bifocals for one eye and trifocals for the other. A war baby, Meyers was immersed in post-war political and military ferment. He collected metal with his mother during the Korean War, watched Victory at Sea on television and learned about the Cold War in school. By 1958, “I was clearly primed for the military. I didn’t know it then.”

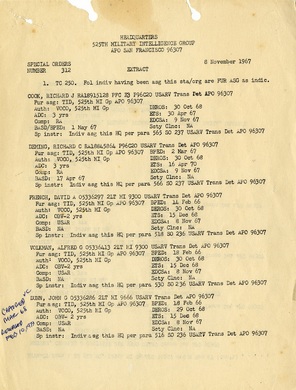

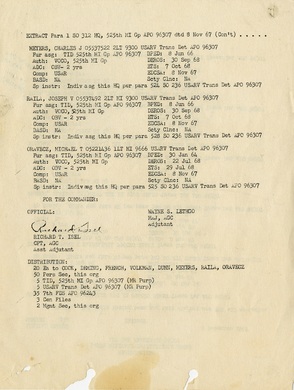

Meyers attended DePaul University. He enrolled in the ROTC program. His father supported it “even though, he realized there was a possibility to go to Vietnam,” Meyers says. “But, I think, in some ways, I was his voice.” Commissioned an Army 2LT on the same day he received his B.A. in History, Meyers attended the Infantry Officers Basic Course at Fort Benning, Georgia from October 1966 through December 1966. Designated an intelligence officer, he took the Intelligence Officers Basic course followed by the Counterintelligence course at Fort Holabird, located at the time in Baltimore, Maryland. He was then stationed in Omaha, Nebraska, in a field office for the 113th Military Intelligence Region. Meyers conducted security clearances and worked with local intelligence resources in 1967 as tensions rose over conduct of the war and civil rights.

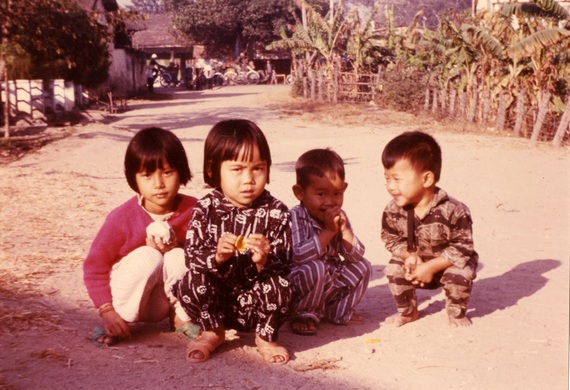

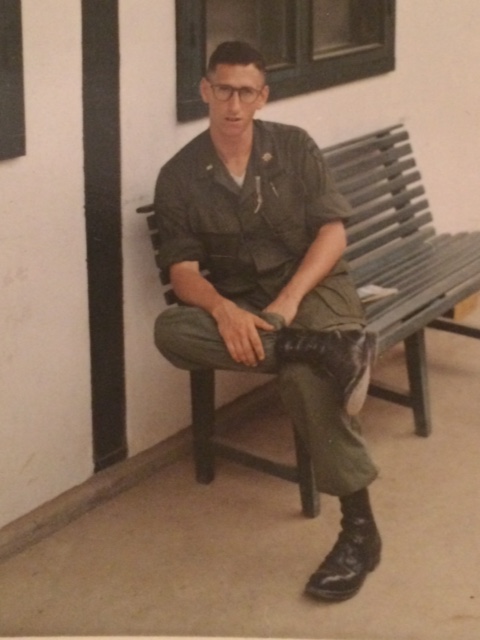

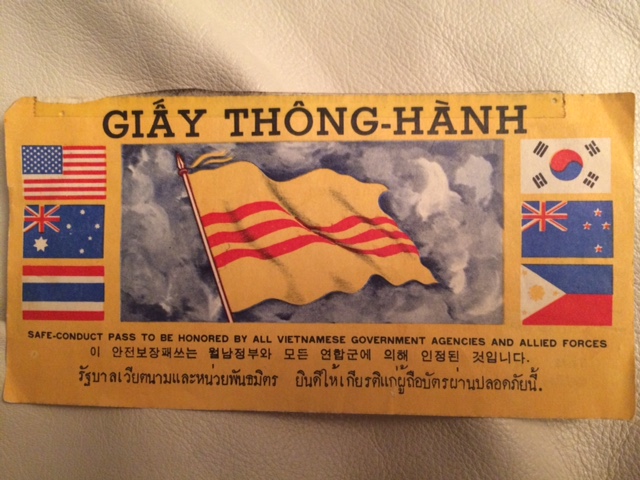

After receiving orders, Meyers arrived in country on 1 November 1967. Assigned to the 24th Special Tactical Zone (24th STZ) located near Kon Tum City, Kon Tum Province in the Western Highlands, Meyers advised the South Vietnamese intelligence units. 24th STZ American and Vietnamese intelligence units shared a barracks-like office. Constant suspicion, fueled by rumors that information shared with Vietnamese intelligence operatives found its way to Viet Cong/North Vietnamese hands, created enmity between allies. “When I arrived there, I was told by the guys I replaced, 'don’t tell them anything... It’s going to end up in the hands of the Viet Cong'".

As a 24th order of battle officer, Meyers monitored Ho Chi Minh Trail truck and troop traffic. By the end of January, it was apparent that something big was about to happen. His unit notified their superiors of an impending attack. Their concerns were disregarded.

Attacked the day before the remainder of the country came under siege, Tet helped change Meyers’ idealized vision of American involvement in Vietnam. “I was there for twelve months. The VC/NVA were there for the duration. Something is wrong here.”

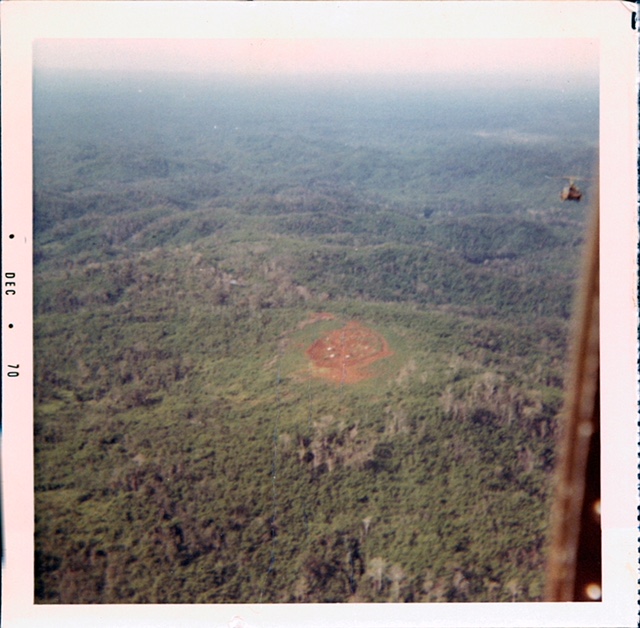

Shortly after Tet, Meyers was transferred to a classified and short lived unit called the Combat Intelligence Battalion (Provisional). Attached to the 1st Infantry Division and assigned to the 2/16th Infantry Battalion in the “Catcher’s Mitt” north of Saigon, Meyers’ three person team used electronic sensors to detect enemy activity along infiltration routes. He rotated to the States at the end of August, landing in Chicago on the second day of the Democratic National Convention.

Meyers received a Bronze Star for his service. He envisions his award as the “thanks for being there” medal. He married his fiancé two months after his return from Vietnam. After earning his Master’s degree two years later, he began teaching history in Elk Grove Village, Illinois. He has one daughter, two grandchildren, and a grand dog. His grandchildren call him on Veterans Day to thank him for being a Vietnam veteran.

Meyers began speaking to students in 1982, the 14th anniversary of his return from Vietnam. He has two suggestions for young people. First, examine your own beliefs. Am I doing the right thing? Second, speak out when you know something is wrong.

He counsels his audiences to carefully analyze information from the government and the media, and to understand what it means to be an American. In retrospect, Meyers quotes The Who, “We won’t get fooled again.”