Record date:

Burton J. Johnson, Major

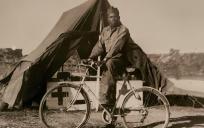

From driving a motorcycle in the Military Police at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to being placed in charge of Japanese P.O.W.s by General MacArthur in Manila, Burt Johnson served his country to his fullest ability at the height of the Pacific Campaign in WWII and was rewarded with promotion and recognition for remarkable service--service that would continue with a life-long career as a lawyer and as one of the original players at Defense Research Institute.

Burt Johnson decided to join the Army at age eighteen and was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. He was placed in the artillery division as a private until the colonel there heard that he had motorcycle riding experience. Mr. Johnson was then put on a motorcycle to drive junior officers around and control traffic before he was promoted to sergeant and put in charge of the motorcycle patrol of Fort Sill.

After the quick promotion, Mr. Johnson remained in Oklahoma for a couple of years, until a colonel urged him to go to Officer Candidate School and be commissioned as an officer. He received his commission at Fort Benning, Georgia, where he focused on infantry training. Mr. Johnson’s commission was changed, however, to corps military police even though it was formed after he completed his training. The reason for this change was that his superiors saw fit to keep him in a similar line of work, now as a second lieutenant. He also was an instructor at the corps military police training and was promoted to captain.

When the time came, Mr. Johnson was shipped overseas to the South Pacific. After the American and Australian invasion of New Guinea, he was sent to New Guinea. He was in charge of all of the Japanese prisoner-of-war camps around the cities of Finschhafen and Hollandia and was the commanding officer over the American and Australian forces in the area. Mr. Johnson also had the job of preventing Japanese raids from the mountains into the villages as well, as organizing the villages and setting up the military police throughout the villages.

Mr. Johnson’s duties expanded again, and he was then made the head of all of the prisoner-of-war camps up through New Guinea, the Philippines, and the small islands thereabout. He established and organized POW camps all throughout the region, followed by a promotion to the rank of major. He was sent to Manila, Philippines, and in the fall of 1944, General MacArthur appointed Major Johnson to be in charge of the north and south bay harbors at Manila—harbors that were being brought in to support the invasion of Japan. However, with the surrender of Japan in the late summer of 1945, the war ended, and Major Johnson was able to go home quickly. He then worked through the OCS school in Oklahoma and was in charge of seeking non-commissioned officers to become a combat battalion while also completing an advanced degree in law. Mr. Johnson was transferred down to Dallas, Texas, and in 1950, his battalion was sent to Korea without him, ending his service in the military.

Mr. Johnson uses his interview to provide details about his unique duties in the Army, about controlling POW camps and using prisoners for labor. He also discusses his relationships with the natives of the Pacific islands, and with the Australian Army; of protecting the supply chain, of protecting and organizing villages liberated from Japan, and of attending special events for officers. His command expanded from six motorcycle riders to a company of 150 military police, to the entire military police force in the Philippines and New Guinea region. Mr. Johnson’s story gives a unique perspective of an American Army officer and how dedicated soldiers like him contributed to the victory of the Second World War in the Pacific.