Record date:

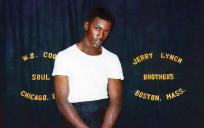

William "Bill" Barron, Lieutenant. US Army. Air Force

The Latin root of civilized "… befitting a citizen…affable, courteous” is an apt moniker for citizen soldier, Lieutenant William Barron. Not only did Barron navigate thirty-two air missions in World War II but strives to navigate life with a moral compass, too.

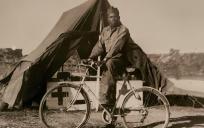

Born in Latrobe, Pennsylvania in 1925, Barron enjoyed a close family, his studies, as well as his scouting activities. Politics were not discussed with children although his father was a WWI veteran and grandfather, a Minuteman before that. The attack on Pearl Harbor caused the teenage Barron to realize that his military service would be a matter of “when” rather than “if.” After he completed a year at Grove City College, Barron joined the Army Air Corps and was whisked off to basic training at Greensboro, North Carolina. In addition to his initiation in the Army, it was also a shocking introduction to segregation in the South.

Since Barron already had some college under his belt, he trained with a group slated to become officers at Cochrane, Georgia. He realized there that he preferred navigation and the related math and science versus piloting a plane. Military training at other bases included Morse Code and rifle shooting. A highpoint for Barron was studying at the country’s best navigation school, in Coral Gables, Florida, managed by Pan Am. It was there where he learned to navigate over water, no easy feat since there are no fixed points such as mountains.

“...the sextant measured the altitude of bodies above the horizon. And then you had to use tables and calculations to get a line of positions... to do a three-star fix. So you'd wind up with a triangle of lines in position…if you had a fairly nice triangle, the idea was you were right in the middle.”

He was introduced to his crew and to their airplane, a B-17, at MacDill Field, Florida, where they had opportunity to practice. After voyaging through Labrador and Wales, he and the crew arrived at Mendlesham Field in England, in September 1944. There was much camaraderie and friendly ribbing. Indeed, the pilot became his friend, travel mate to London for their brief stints, as well as his future brother-in-law.

Of course, it was not all fun and games and Barron recounts some harrowing times. For example, on a mission to Wurzburg, a German fighter plane, a FW-190, fired at his B-17 with a 20 mm cannon. Barron did his best, shooting an old .50 machine gun where every fifth round, a tracer which would produce a red glow, that had a likeness to a stream of bullets. Fortunately, that scared away the FW-190.

His plane was not so lucky when on a mission to Berlin. The two engines, the regular compass, and part of electrical system were knocked out by flak. Not surprisingly, the drag was slow, and the plane could not keep up with the formation. A fighter aircraft, a P-38 escorted his plane out of the battle area but after moving further north, it was clear that there would not have sufficient fuel to cross the English Channel. Luckily, the crew encountered a flock of flock of Hawker Typhoons from Anzac who were landing at Eindhoven, Holland, then liberated, who led the way.

Barron was also witness to the horrors of war. Anti-aircraft fire hit a “next door” plane during a mission to attack Peenemünde, a German submarine base. Sadly, there were no parachutes and one of the casualties was his former co-pilot.

It should be noted that there had been a scrubbed mission which led to the break-up of the original crew. The command to abort was sudden, just after setting forth on the English Channel. The pilot who was extremely skilled, unfortunately, miscalculated the speed for a sudden landing. He did have the presence of mind to turn off the master electrical switch which prevented the plane from blowing up. This led to a disciplinary measure against the pilot and break-up of the original crew and subsequently Barron flew with other crews.

Barron also experienced empathy for those for whom the war took its psychological toll. For example, he recalls the short gunner who had been squeezed into ball turret, screaming in terror. The radioman released him to another part of the plane, covering him with flak jackets to soothe him but he spent the rest of the war on kitchen duty.

Subsequent knowledge has led to some difficult reflections. Although Barron and the others were not privy to strategic information, he regrets the mission to bomb Dresden, Valentine’s Day, Feb. 14, 1945. The city had already due to RAF firebombing the previous night before his squadron arrived. Similarly, he was dismayed to later learn that on a mission to support troops on the front line, drifting smoke obscured the bombing line such that the plane was the cause of friendly fire.

Barron was shipped out on March 1945 before VE Day on a troopship that was part of a convoy escorted by British corvettes. After his separation from the Army in October 1945, he went to live with his sister and brother-in-law in Erie, Pennsylvania, happy to let of steam at a job of shoveling sand before he left to study mechanical engineering at Carnegie Institute of Technology.

Barron was obligated to be on “Inactive Duty” after his separation from the Army and was recalled to active duty in 1951 due to the need for instructors of air crews during the Korean War. He studied at the Instructor School for Navigators in Ellington Field, Houston and was then assigned as a B-29 instructor for training missions at Randolph Air Force Base in Texas.

Barron married, raised a family, and worked in the realms of engineering as well as in sales and marketing realms in Milwaukee and elsewhere, before retiring to Chicago. He considers himself lucky as well for having come out physical and mentally intact from the war itself, though it certainly was a sobering experience. Barron questions America’s increasing involvement in wars, especially in Vietnam and in Afghanistan, mourning the tremendous waste of lives. He also resents militaristic trends in Germany both then and now. He advises the teaching of Civics again so that the young will understand that democracy is not a given and that it requires work to maintain it.