Record date:

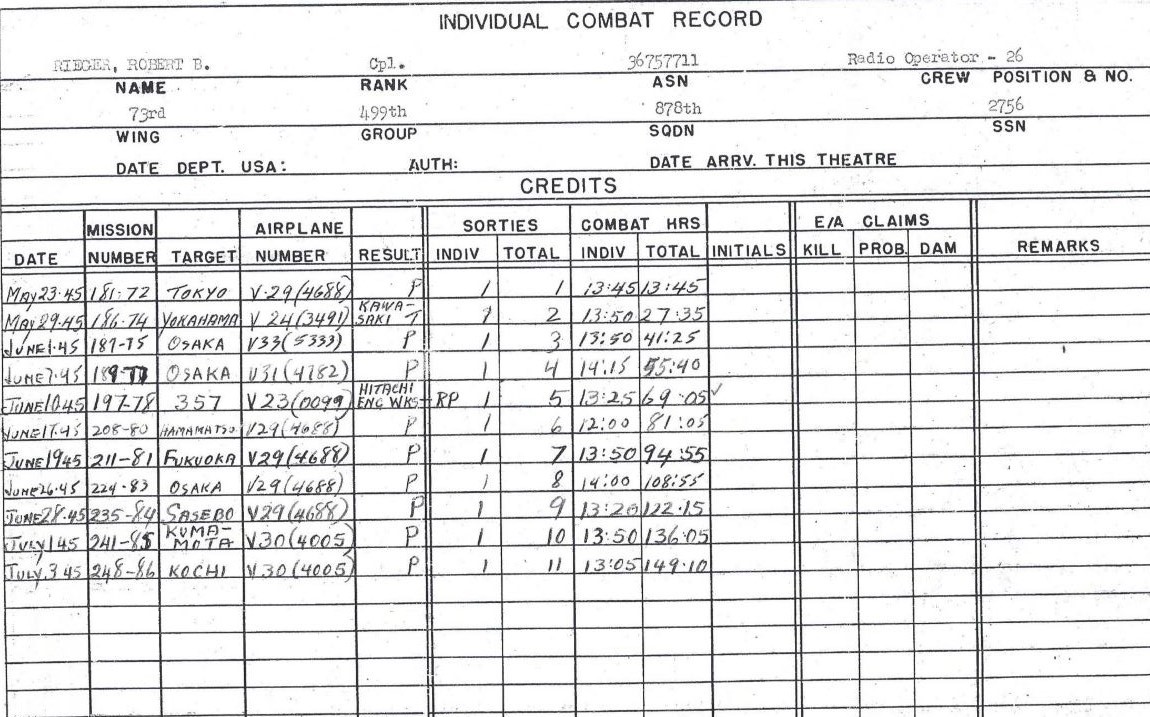

Robert Rieger, Corporal, US. Air Force

Whether mastering or relaying messages in MORSE code on low-altitude firebombing raids of Japan, Corporal Robert Rieger’s vigilance never wavered.

Born in 1923, Robert and his parents did not experience the hardships of the Depression until 1936 when his father was laid off from his job at Borden’s Milk. Aside from a short attempt to settle in California, his family generally lived in the north side of Chicago.

Rieger enjoyed studying at Lane Tech high school, especially participating in the school orchestra. On his initiative, he took lessons from a former violinist of this orchestra and continued to play in gigs until he began his military service. He studied at Wright Junior College and approached the draft board asking for a six-month extension to complete his two years. His application to the Army Air Force was accepted.

Shortly after graduation, in July 1943, he reported to basic training at Miami Beach. After a few months of dealing with prickly heat and getting accustomed to discipline, Rieger was sent to West Virginia University in Morgantown where he studied Aeronautics. One highlight was mastering how to fly a two-seater Piper Cub.

Since the Army needed to better determine the individual’s strengths to assign his military occupation, further testing was carried out in Nashville, Tennessee. Rieger noticed that the relatively speaking older guys tended to be chosen as pilots. He was assigned to six months of study at the Radio School of Scott Field, Illinois to become a radio operator and mechanic. He also volunteered for the training of radio operators who were to serve on the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, then the cutting-edge aircraft. As was the case in Virginia, Scott Field also offered Rieger and the other men opportunities to meet local women and he began to date a woman while stationed there.

Next crews were to be established at Pyote, Texas. Rieger was invited to join one as a radio operator. The crew flew on many practice missions over the country. After five months, the crews were sent to Topeka, Kansas. Their last stop was Mather Field, California from which they would disembark, heading to the Pacific Front. They landed in Saipan, one of the Northern Mariana Islands, in April 1945 shortly after it was secured by the US.

Rieger describes some of the eleven bombing missions in which he took part. His first mission occurred two days after his birthday, on May 23, 1945, when the crew was charged with dropping incendiary bombs on Tokyo. He recalls that on a few missions, there would be a rendezvous of about 300 planes from various Mariana Islands, about 100 to 150 miles away from the coast of mainland Japan. As much as the Japanese air force was destroyed at this point, the B-29s were not home-free. They were exposed to anti-aircraft fire, especially because they were flying at a low altitude of 8,000 -10, 000 feet to carry out precise bombings of targeted buildings. Kamikaze attacks such as the ramming of Japanese aircraft into theirs were also a threat.

As a radio operator, he typically received reports on weather conditions, and whether there would be fighter support from Iwo Jima, which was in US hands by the end of March 1945. The landing fields of Iwo Jima were critical for B-29s since the plane did not always have sufficient fuel for the return flight to Saipan from Japan, it being over 1200 nautical miles away. Rieger discusses his crew’s emergency landings at Iwo Jima due to a fuel leak or to loss of an engine.

On the return flight, Corporal Rieger would “listen for B-29s in trouble”. For example, if he detected that a B-29 sent an SOS message to the base in Guam which was not received, he would re-send it. Communication was altogether challenging with the enemy trying to jam up the messages or the need to tediously transmit four or five words at a time to avoid detection.

Rieger also describes preparing for a mission from inspecting the aircraft, and the radio equipment to setting up frequencies on the transmitter-receiver. The crew would then go to the hangar for their harnesses and parachutes while the ground mechanics would test the engine.

Usually, the tension of an anticipated mission the next day would preclude sleep from Corporal Rieger. He is frank about his losses, “All you know is there’s an empty bed in your Quonset hut that night.” He would be thus awake for thirty hours until his return to Saipan. The relieved crew would be rewarded with coffee or booze and a steak dinner.

Their last mission was to fly back to the United States in mid-July. Rieger was to report to Mather Field, California after a furlough. Since VJ Day occurred in August, fewer personnel were needed, and he was granted forty-five days of R & R. After reporting to Santa Ana, California at the prescribed time in September or October, it was realized that he qualified for a discharge since the number of points required had been reduced. He separated from the Army Air Force in November. His time with the 73rd Wing, 489th Group, 878th Squadron, 20th Air Force came to an end.

In his civilian life, Rieger worked in various positions cycling up to ever higher levels of management in different companies. He attributes his good work ethic to his military service.

Rieger married the woman who had been his girlfriend at Scott Field, and they had two sons though it was a short-lived union. Later, he remarried, and the couple had a daughter who helped them in their advanced senior years.

Although Corporal Rieger was disappointed that his rank was not raised to staff sergeant during his tour in Saipan, as promised, he is proud to have served in the US Army Air Force and to have contributed to the US’s war effort.