Record date:

Michael Vlamis, Sergeant

Born in 1929 in the town Kalyves, on the island of Crete, Michael Vlamis’ childhood would be one governed by uncertainty and later war. As an adult, war knocked on his door twice, the second time drafting him into US Army, during the height of the Cold War.

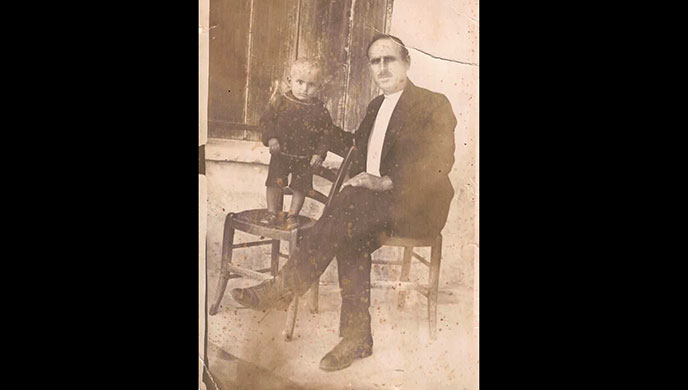

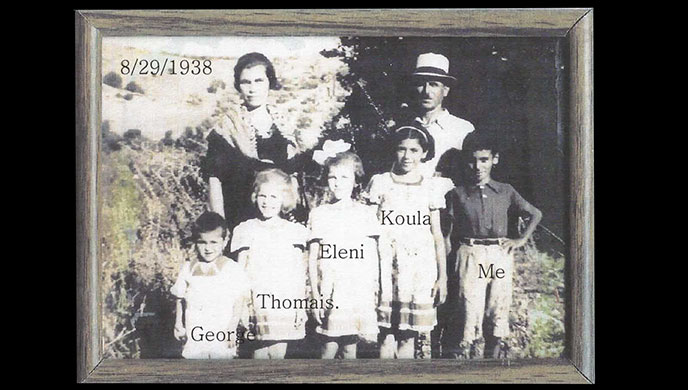

In spite of the anomalies living under the dictatorship of General Metaxas, Michael’s earliest years were pleasant. His father who had lived in the US for many years, established a thriving agricultural business in Crete. The family home was located above the scenic Souda Bay. Michael and his four siblings grew up in the arms of a warm extended family and community.

Yet, being so close to Italy, one could not be blind to fascism. On August 15, 1940, the Italian submarine Delfino torpedoed a Greek cruiser Eli. On October 28, 1940, Italy which now occupied Albania attacked the neighboring Greece, but was forced into retreat. Shortly after that, events hit even closer to home with almost daily air raids on Crete from the nearby Italian occupied Island of Rhodes. Michael then witnessed the British defense efforts setting up two high caliber cannons at the port. The Nazis attacked Crete on May 20, 1941, less than a month after the fall of mainland Greece. The Vlamis family, and others, hid in abandoned caves at night to protect themselves from the relentless bombing and strafing. The Germans were incensed by the civilian resistance in Crete, some of whom aided the British, and they unleashed a vengeful collective punishment, such as the executions of all male townsfolk of Kondomari, and other villages.

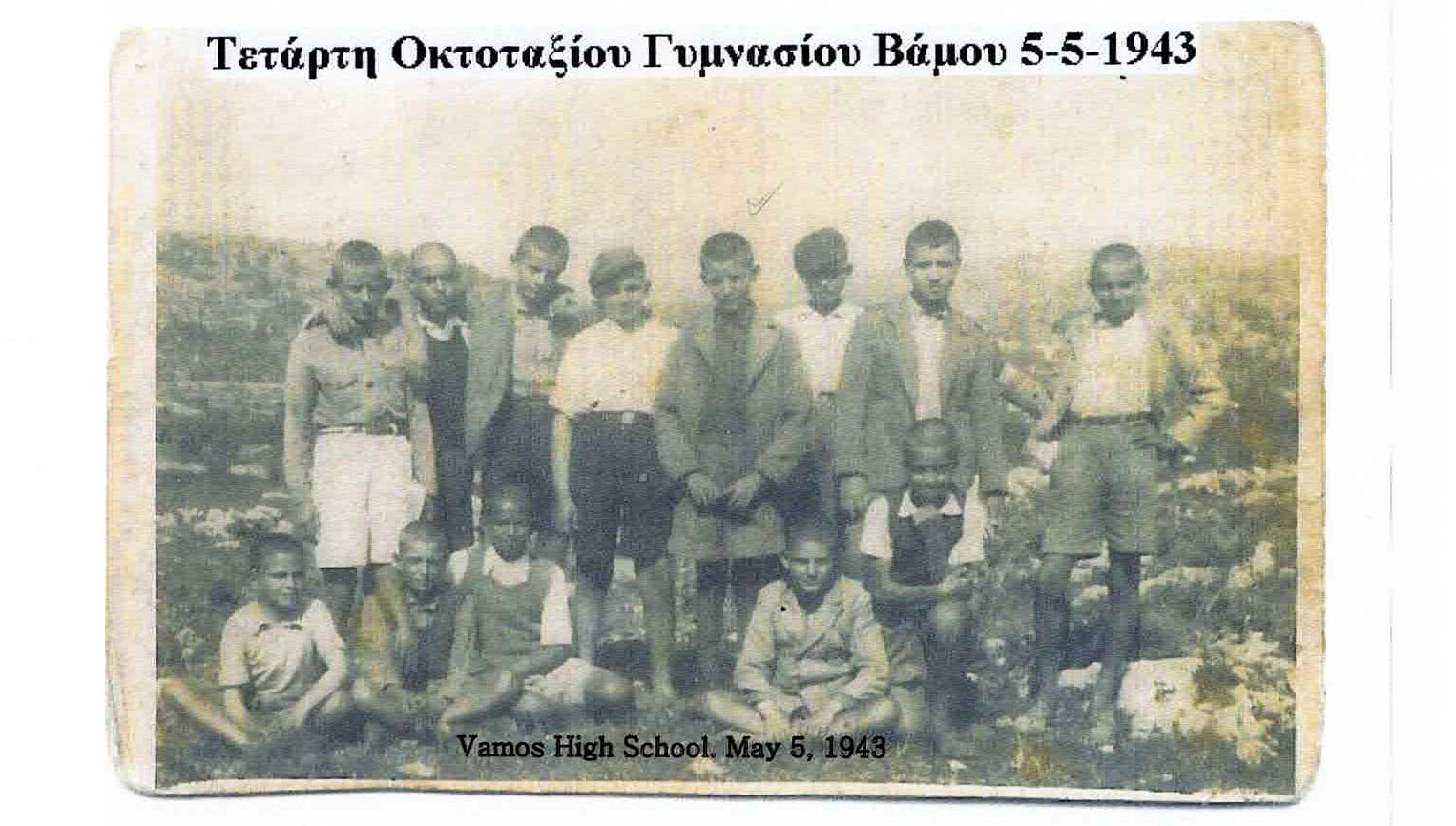

The courageous spirit was manifested in the children, too. Mr. Vlamis describes how the German soldiers driving to villages to pick up workers offered the children rides to school about eight miles away in exchange for some eggs. One day, however, the drivers only offered the girls a lift. All the students refused the transportation, and showered the drivers with more than twenty eggs the next day. The Germans immediately stopped and offered them rides but again all sixty-five students refused. The drivers were furious yet, the next day they allowed all the students to alight.

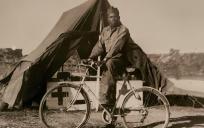

An ambitious student, Michael experienced the disruptions due to the occupation as deviations from his chosen path. His memoir is aptly entitled, “A Detour in My Life.” He, like many others protesting the Nazi occupation joined EAM, [acronym in Greek meaning, National Liberation Front] not realizing that it was controlled by the communists. Aside from being tasked to steal bikes from the Germans, his friend provided him with ideological literature, encouraging Michael to recruit others to the movement.

Daring acts, carried out by the British SOE [Special Operations Executive] who arrived secretly on Crete via submarines or boats, in collaboration with local guerillas lifted the population’s morale. The prime example was that of the kidnapping of German General Kreipe by SOE agents, Leigh Fermor and Stanley Moss, in which Kreipe was spirited off to British controlled Egypt. Throughout the occupation Michael and his family lived their lives with spirit. For example, they were complicit in their tenant’s decision to shelter his son, wanted by the Gestapo, and later aided in the latter’s escape. Procuring food, especially during 1941-42 when hunger was rampant was also fraught with risk. The Nazis briefly jailed his mother and later his father. His crime was having bought beans from a torpedo ship.

Vlamis was shocked by Nazi cruelty such as their refusal to feed their captured Australian and New Zealanders prisoners of war. He recalls distributing bread to them and witnessing a large Maori man with no limbs crying, unable to procure any food. Michael asked his neighbor to provide some bread for the unfortunate man. Vlamis was witness to horrific events such as the burning of the Nazi USS Tanais, torpedoed by the British, whose passenger were comprised of Italian and Greek prisoners and Jews from Chania.

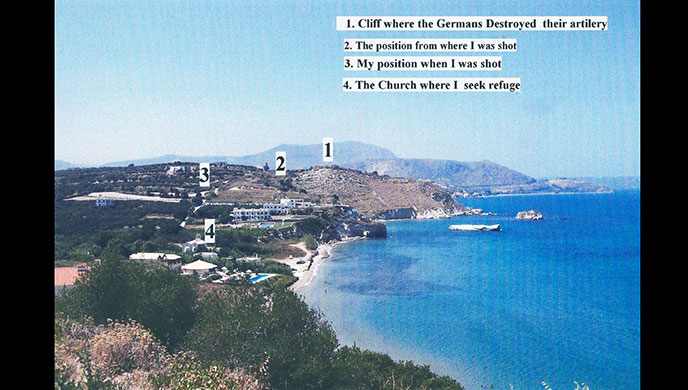

The war ended dramatically for Vlamis. He ran to pick up rubber from canons which the German had exploded right before their departure, but he slipped and fell. One German took a shot at him. Vlamis ran away and hid in a church for a few hours until it became quiet. He then walked home, expecting to see celebrations of freedom. Instead, he found his compatriots arguing about politics!

After graduating high school in 1947, Vlamis studied at a college of commerce but due to the Greek Civil War, his draft was imminent. For this and other reasons, he decided to avail himself of the opportunity to immigrate to the US afforded to children of American citizens.

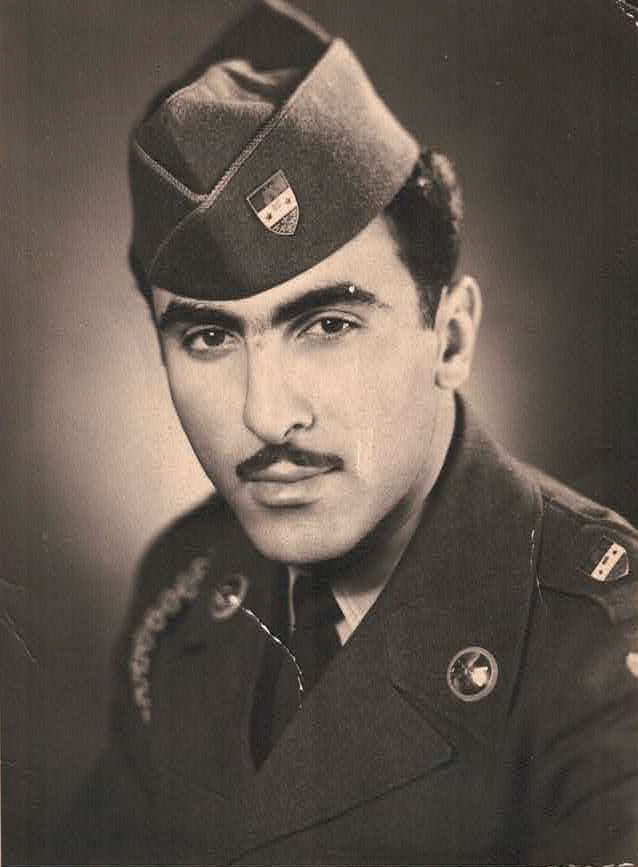

In 1950, shortly after the Korean War began, the US Army attempted to draft Michael, but he pretended not to speak English and was given a two-year deferment. When time was up, he served in the US Army and began a four-month training with the 101st Airborne Division in Kentucky. He was then shipped to Germany, serving with the 7th Army, 28th Infantry Division, 110th Regiment, 2nd Battalion, Company H.

Vlamis arrived in Germany on June 17th, 1953, the day of the East German uprising against the Soviets. He and his unit were rushed to a small warehouse, given rifles, and instructed to be on alert.

After three days, he was assigned to Ulm, Bavaria, near the Czech border where he served for eighteen months.

In January 1954, Vlamis was sent to school to train as an NCO Non-Commissioned Officer for six-weeks and then led a squad of about twelve people. Two months prior to his discharge was promoted to the rank of sergeant. Vlamis who was already in good physical shape was open to rigorous training. He also mastered the necessary ammunition such as the recoilless rifle, and especially enjoyed meeting Americans from all walks of life. One highlight was saluting the famed General Ridgeway.

After Vlamis’ discharge on November 30th, 1954, he immediately signed up for the electrical engineering program at the University of Illinois. Vlamis married when finishing school and raised a son and three daughters. After graduation, Vlamis began a successful career in electronics. Mr. Vlamis reflects that although growing up under the occupation was rough, it gave him the resilience to face life’s challenges. Ultimately, he is grateful to the United States, not only for the education that he received through GI Bill but most of all for the freedom of living in a democracy.