Record date:

Joseph Schvimmer Transcript .pdf

Jospeh Schvimmer Addendum to Transcript

Joseph Schvimmer, Colonel

Colonel Joseph Schvimmer is listed in Silent Heroes & Their Aircraft. U.S. Marines and Airborne Electronic Warfare, 1949-2019 for flying four-hundred and fifty missions. Yet this does not even count his helicopter flights when he was in the US Army Reserves. Nor does it give a nod to his fighting in combat infantry nor playing “electronic chess” to jam missile systems. Schwimmer’s agility and ability to solve problems of any kind both in the military and in civilian life are non-pareil.

Joseph Schvimmer was born in 1938 and grew up in New York and New Jersey to Jewish immigrant parents. Largely inspired by his uncle, Schvimmer decided to enlist in the US Marine Corps after he graduated Temple University in 1962.

After intensive flight training, he was assigned to VMCJ, Marine Composite Reconnaissance Squadron Two, at Cherry Point, North Carolina, which focused on electronic warfare where he analyzed and located radar signals. He would jam the operation of HAWK and SAM missiles and then confuse the human operator. VMCJ expanded the airplane capabilities for electronic warfare of anti-aircraft missiles. The squadron also monitored Cuba after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

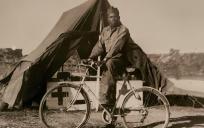

Schvimmer was deployed to Vietnam in October 1965, and he and the others improvised a camp near Da Nang. There he flew several missions daily as part of Rolling Thunder, aerial bombardment against North Vietnam, China, and North Korea. He was assigned to the 7th Air Force headquarters to write the night fragmentary order, the immediate adaptation to the operational plan for the reconnaissance flights of Rolling Thunder. He flew missions for Iron Hand, an action intended to suppress SAM missiles in North Vietnam. He also flew planes such as RF4B for photo reconnaissance and accepted missions were done on behalf of other forces. Schvimmer received an air medal, among his numerous air medals, from the Secretary of the Navy “for heroic achievement in aerial flights…of two…hazardous assignments escorting electronically supporting a Navy aircraft…deep into North Vietnam.”

In spite of all the time in the air, Schvimmer’s collateral duties included ground patrol and security at Cam Lo to Hai Van Pass. He recalls being part of a group of five and seeing twenty-five enemy soldiers in one instance. After the tour, he returned to North Carolina and was reassigned to VMCJ -2. He relished flying the four aircraft Skyknight EF10-B, Grumman EA 6A, Prowler EA6 A & B, and Phantom F-8 Indeed, the Marine Corps Reconnaissance Association later used his photo of all four planes.

In 1969, Schvimmer was deployed to Vietnam for his second tour, at a now built-up Da Nang base. Although the Vietnam War, in general, was winding down, t there were far more SAM missiles. Thus, the VMCJ were highly motivated to fight and employ their more powerful plane, EA-6A. Ironically, during his second tour, Schvimmer was taken off the air and put in infantry. At a major battle near Con Tien, where the 3rd Division was fighting, he had to take charge when the company commander was killed. He was quick to realize that they needed to form a semi-circular defense and led with the goal of minimizing losses.

Schvimmer himself was wounded when a lone North Vietnamese gunner shot between the cockpit of a TA-4 aircraft when they were flying over. Xepon, Laos. He parachuted in a dry riverbed and his friend landed in a tree. Even while waiting to be rescued the next day, Schvimmer had to contend with enemy soldiers. Schvimmer’s ingenuity extended to his personal life. He noticed during his second tour that when flying on RF-4 planes with low radio frequency, he could connect with a radio amateur in the US and/or get a landline with his wife in the US.

During both tours, he accepted cast-off missions from other forces, including photo reconnaissance ones from the Air Force during his second tour. He and his friend Gary, also Jewish, had a mission at Mụ Giạ Pass where there were guns on both hills. They carried out successfully in an RF-4 plane adorned by a Star of David, and were escorted by a Phantom, flown by another Jewish pilot, Dave Levine.

After Schvimmer returned in 1970, he was attached to the Fleet Intelligence Center as a secondary Intel officer with a focus on amphibious warfare. One highlight was leading a team to plan for an attack on Haiti which he realized would be likely after Papa Doc Duvalier’s death. Teaching at the Fleet Intelligence Center and similar institutions occupied him until about 1975.

He then worked at various jobs as a civilian from a supervisory engineer in Norfolk Dredge to managing restaurants. He was then hired by the US Civil Service in the Navy Manpower and Materiel Command in Atlantic and Norfolk Naval Shipyard. There he conducted numerous studies on how to make harbors, tugboats, manpower, etc. more efficient and became an expert in analyzing personnel issues. His work helped uncover theft in harbors and he joined NAVSEA Naval Sea Systems Command, in Washington where he created a new standard of locks for storage facilities for ammunition. Schvimmer then worked for the storied and supportive Admiral Rickover as security inspector for the shipyard. For example, he uncovered the fact that 89% of the fuel arriving in shipyards of Portsmouth was being used by locals.

Around 1979, Schvimmer joined the Army Reserves. He served as a warrant officer in charge of a photo Intel platoon, in Alconbury England. The following year, he recruited men in Washington, DC to form the 223rd Military Intelligence Battalion who were sent to the field in Virginia. Similarly, he later recruited photo interpreters from DIA [Defense Intelligence Agency], who were deployed to Zweibrücken Air Base, Air Force. Other roles include being a helicopter pilot or inspecting nuclear production sites. Because of his helicopter ability, he started to work for the Department of Energy and was the head of its helicopter security operations. He retired from there in 1998.