Record date:

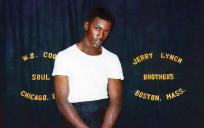

Deane Stanley “Stan” Moore, Corporal

Corporal Moore, the soldier, studied Russian during the Cold War in order to intercept enemy messages. Yet for Stan Moore, the civilian, Tolstoy’s tongue became an instrument of peace.

Moore was born in Minneapolis in 1929 and recalls a benign childhood where the family managed during the Depression. The family followed the news of World War II even on shortwave radio, and his father a World War I veteran, volunteered as an air raid warden.

Moore majored in History at Beloit College, graduating in 1951. He decided to enlist for three years rather than be drafted unexpectedly. Since he did well in the Army’s aptitude tests, he was assigned to the Army Security Agency, the 328th Communication Reconnaissance Company. Moore attributes his success in the artificial language test to his acceptance at the Army Language School.

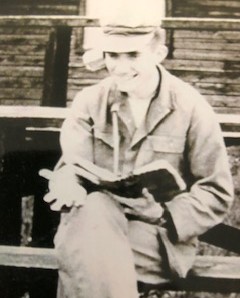

After he “endured” the eight weeks of basic training in Fort Riley, Kansas, and after a short stint at Vint Hills Farms Station, Moore headed out to the Language School, at Monterey, California. This intensive forty-six weeks Russian language program turned out to be a pivotal moment in his life. He found both the pedagogic method as well as the teachers excellent. Moore also enjoyed colorful aspects such as a teacher who reinforced the rumor that he was a descendant of the Romanov royal family. It was there when Moore was assigned his MOS, military occupation specialty, as Voice Intercept Operator. The next step was to improve his typing skills at Fort Devens, Massachusetts. Then, in 1953, after an uncomfortable voyage on a troop ship, Moore and his group arrived at their destination, the 328th Communication Reconnaissance Company, a US base at Bad Aibling, a Bavarian spa town with a view of the Alps.

In the 1950s, Russia occupied then Lower Austria and Czechoslovakia. As a result of Cold War tensions, Moore and his group were assigned radio interception of these targets. In practice, this meant, sitting at the short-wave radio, constantly turning the dials in hopes of hearing enemy traffic such as conversations between pilots and tank commanders. Once a Russian phrase was heard, they would immediately translate it into English and type it in a report to their superiors. For about one month, they worked in the field, closer to the Czech border near the Inn River.

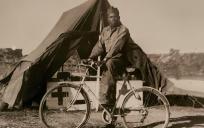

While in Germany, he observed that although the locals did not seem to be afraid of an imminent Soviet invasion, they did hope that with the passing of Stalin, Russia would become less aggressive. Moore found the people friendly, and grateful for the business while their kids were pleased about receiving candy from the soldiers. In his spare time, Moore would take German classes offered to the 328th, play piano for religious services, and read classics such as War and Peace. He and his friends enjoyed outings to Salzburg and Vienna. Moore valued the cooperation he witnessed in Vienna, then administered by the Allied Control Center, such as jeep patrols composed of Russian, French, British, and American soldiers. Not relishing the return trip on a troopship, he applied for an overseas discharge. He thus bought a bike from the PX and after his discharge, cycled to England to visit his aunt and uncle before going back.

When he returned to the US Moore used GI Bill to do a master’s degree in Russian Area Studies at the University of Minnesota. His thinking was influenced too by courses taught by Professor Mulford Sibley, a conscientious objector. Moore decided on a career as a teacher and met his wife, Jan, also a teacher at a school in Park Forest, near Chicago. With the US concern triggered by the USSR launch of Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit earth, some schools began to teach Russian. Moore began to teach this language, in addition to English and history. He places much value on living in a democracy where he had the freedom to choose textbooks that he saw fit.

In the 1970s, he participated in two Russian-American teacher exchanges. He was selected to study Russian at Moscow State University for ten weeks in a program sponsored by the US State Department. During the second exchange, he taught English in Special School # 9 in Moscow for one month and School #238 in Leningrad sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee and the RSFSR [Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic] Department of Education. He would introduce American literature to the Soviet students evoking their experiences:

“Those exchanges during the Cold War I felt were…essential to keeping us peacefully together.”

Moore and his family also enjoyed camping trips throughout Russia and Ukraine. Indeed, throughout their lives, Moore and his wife taught students overseas: in Scotland, China, the Czech Republic, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Their enthusiastic global approach was “caught” by their son, daughter, and even by their grandchildren!

Moore appreciates the fact that the Citizen Soldier can dedicate himself to the military for the short term and then can resume civilian pursuits, not to mention his own opportunity to learn Russian. Yet he sympathizes with those who do not want to serve due to moral objections to wars be they in Vietnam or Iraq and Afghanistan. When asked about his thoughts on the planned Cold War Memorial at the Pritzker Archives and Memorial Park Center, Moore shares his harmonious view. It should not emphasize hostility between Russia and the West but rather acknowledge how both are an integral part of Western civilization.