The Armistice

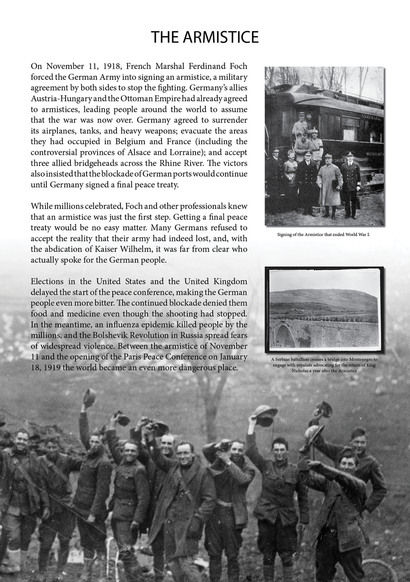

On November 11, 1918, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch forced the German Army into signing an armistice, a military agreement by both sides to stop the fighting. Germany’s allies Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire had already agreed to armistices, leading people around the world to assume that the war was now over. Germany agreed to surrender its airplanes, tanks, and heavy weapons; evacuate the areas they had occupied in Belgium and France (including the controversial provinces of Alsace and Lorraine); and accept three allied bridgeheads across the Rhine River. The victors also insisted that the blockade of German ports would continue until Germany signed a final peace treaty.

While millions celebrated, Foch and other professionals knew that an armistice was just the first step. Getting a final peace treaty would be no easy matter. Many Germans refused to accept the reality that their army had indeed lost, and, with the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm, it was far from clear who actually spoke for the German people.

Elections in the United States and the United Kingdom delayed the start of the peace conference, making the German people even more bitter. The continued blockade denied them food and medicine even though the shooting had stopped. In the meantime, an influenza epidemic killed people by the millions, and the Bolshevik Revolution spread fears of widespread violence. Between the armistice of November 11 and the opening of the Paris Peace Conference on January 18, 1919 the world became an even more dangerous place.