Record date:

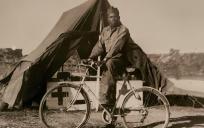

Arthur Koblish, Naval Reserves

As a volunteer for the US Naval Reserve, in late 1942, Arthur Koblish never saw warfare, but, instead, found himself part of the V-12 program, studying at Northwestern University and Columbia University before being shipped to Pearl Harbor, in late 1945. Although he sat on the sidelines during World War II, his time in the military remains a significant element of his life.

Arthur was born in Detroit, Michigan, on February 29th, 1924, Leap Year Day. At the age of six, he and his family moved to the Chicago suburbs. He had a stable life during the Depression thanks to his father, Max Koblish, a graduate of chemical engineering from the University of Michigan. After being laid off, Max started his own business as a repairman of refrigeration units in apartment buildings. Since few people could do this kind of work, he was in great demand. He was able to accumulate enough income to buy an apartment building and eventually retire at only forty-six years old. “That was the beginning of real success for our family,” Arthur recalls.

Koblish enrolled at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, as a mechanical engineering student and later enlisted in the Naval Reserve, in late 1942. He continued his education at Northwestern University, while on active duty with the Naval Reserve V-12 Program, which was designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers in the United States Navy during World War II, as an apprentice seaman. Outside of the classroom, Koblish’s life didn’t differ much from the other civilian students. He had shared duties with the other V-12 members, though, such as standing guard at the Navy’s office at the university.

After Northwestern, Koblish went to Naval Reserve Midshipmen’s School at Columbia University in New York. Shortly after the A-Bomb was dropped in Hiroshima, Japan, Koblish’s term at Columbia ended and he was sent to Pearl Harbor in late 1945. He was assigned to a machinery ship and coordinated the work between the Navy and civilian workforce. Even though the workload was light, he was disappointed that he wasn’t released from active duty after the war ended.

“Well, that was kind of a disappointment because I had been anticipating getting out of uniform,” Koblish recalls. “I never really liked the idea of naval protocols and the way things were done…decisions made…and I think a minor thing that really irked me, having to salute somebody just because he had brass on their hat.”

Koblish was eventually released from active duty in the spring of 1946 and returned to Northwestern to earn his degree in mechanical engineering. He was able to find steady work because engineers were high in demand, and he worked various projects, most notably contributing to the development of the aluminum beer can. Koblish did well for himself, retiring at the age of fifty, and continued his early childhood passion, swimming.

While at Northwestern, Koblish was part of the swimming team. After graduation, he joined a nearby athletic club and started playing water polo, a sport in which he competed for twenty-five years; was in an all American at least ten times; represented the United States in the 1959 Pan American Games at Soldier Field in Chicago, Illinois; and almost qualified for the Olympics. After his water polo career, he competed in the United States Masters Swimming organization and swept the national championships in his age group, that of the eighties.

While he had mixed feeling during his military service, Koblish thinks highly of the V-12 program because it was well organized and accomplished its goals. His primary criticism is not directed to the military, but to the actions which the nation has taken, causing it to require having a large military force.